Webpack module federation for micro frontend implementation: accelerating development, testing and deployment

We share our experience of migrating a monolith app to micro frontends using webpack module federation

Micro Frontends: solving the monolith issue

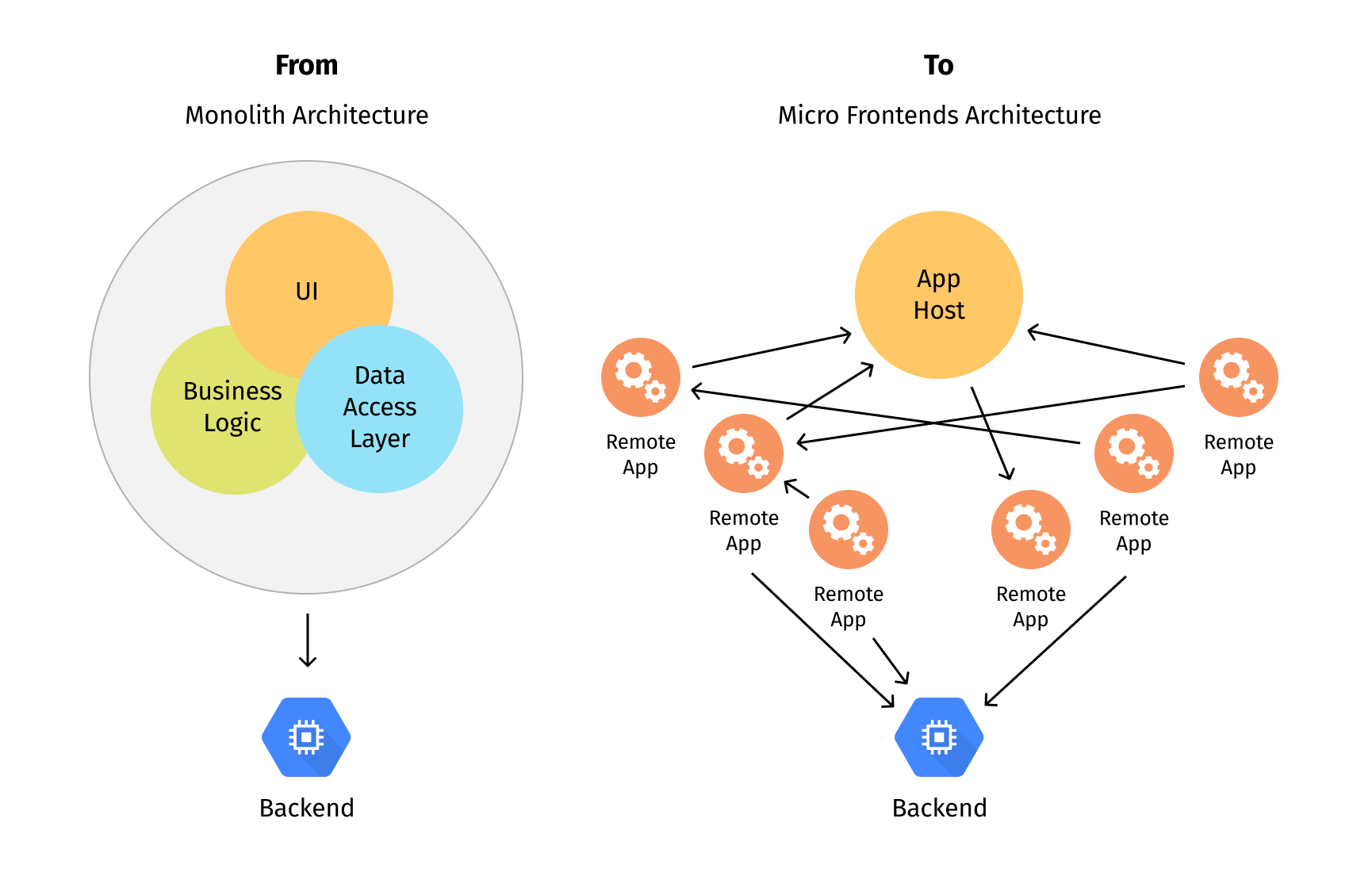

What does a web application usually look like? Most often it is a monolith with a single code base where the whole team merges the code, and a single pipeline where everything is deployed at once and most probably tested at once.

For some projects such an approach is absolutely fine, but what happens when functionality requirements change and the team is too small or too large to handle development demands? In this case, many pitfalls may arise: the time between project release cycles grows, testing time increases significantly, and deployments become frustratingly long.

Besides that, making small changes, adding new functionality or just fixing minor issues are likely to become long, slow, tricky challenges that block developers at every single step.

Furthermore, imagine how complicated it becomes to onboard a newcomer or expand your team? To handle that, you need to understand the entire application flow, all business processes, various code implementations and utilities - things not every business analyst can handle.

As you can see, monolith solutions are hardly feasible for fast-moving, forward-thinking enterprises in the digital age.

How we managed chaos in a monolithic project: a case study

One of the projects we had for a client with a monolith system required us to implement capabilities for effective future scalability. Based on our research we decided to go with a Micro Frontends architecture solution, as it provides capabilities to:

- handle parts of the application separately;

- easily track independent development flow;

- combine ‘old’ and ‘new’ parts of the application; and

- organize partial unit deployment.

As a result, we expected to achieve significant time reductions for development, testing and deployment.

What are micro frontends?

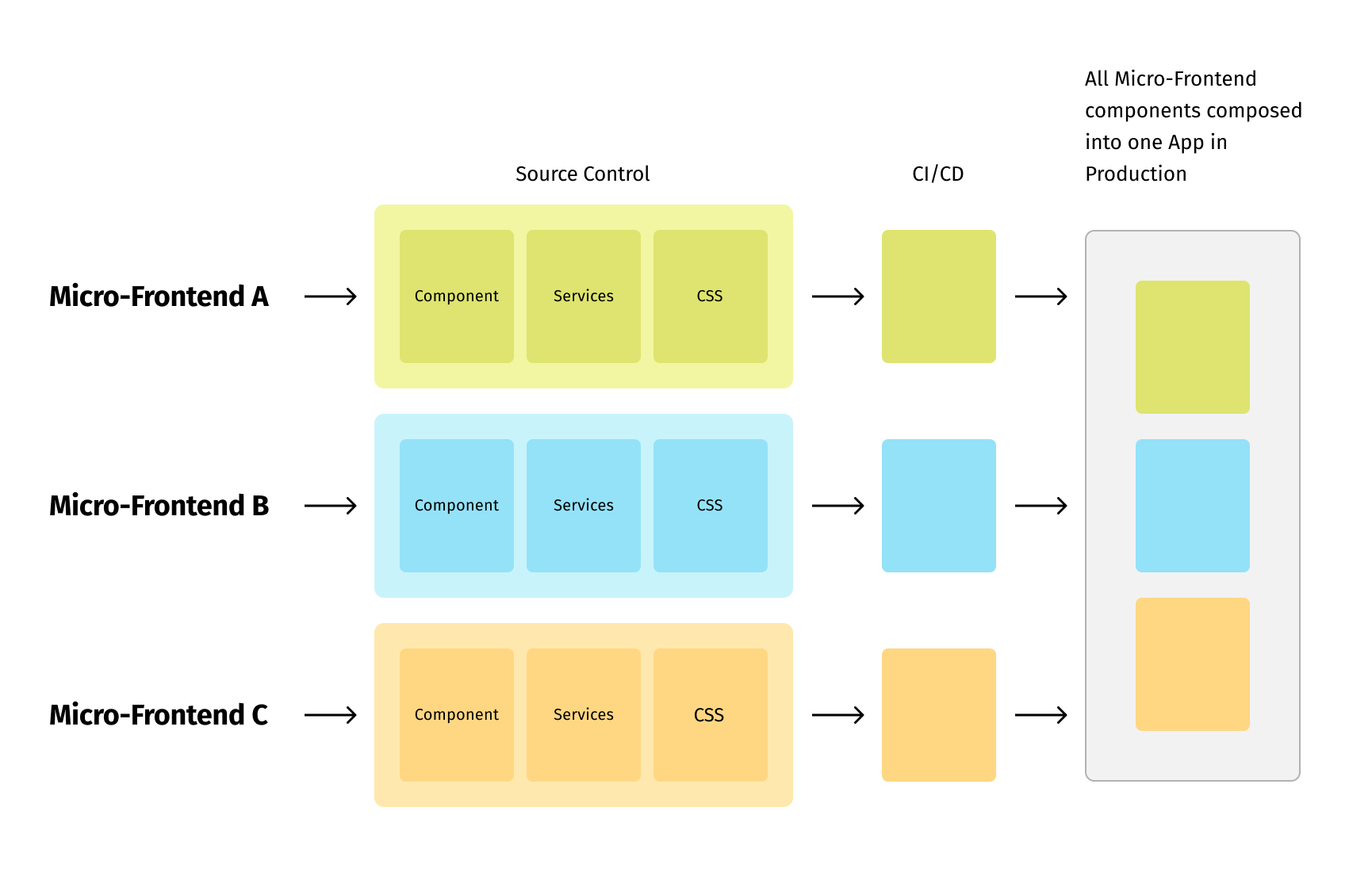

Micro frontends are an architectural approach to frontend web development that involves decomposing frontend monoliths into smaller, simpler chunks that can be developed, tested and deployed independently by different teams using different technologies.

Some of the key benefits of micro frontends are:

- smaller, more cohesive and maintainable codebases;

- more flexible scalability with decoupled, autonomous teams;

- the ability to upgrade, update, or even rewrite parts of the frontend incrementally and independently, without impacting the entire system.

To decide on the micro frontends approach we would take, we assessed the pros and cons of monorepo vs multi repo approaches, as shown below:

Our team decided to split the monolith following the monorepo approach based on the following reasons:

- The code remained in the same repository;

- The styling, interfaces, and dependencies are saved;

- It’s easier to set everything up locally and configure it correctly.

Monolith to micro frontend migration technical challenges

During the migration process, the development team were tasked with the following undertakings:

- Migrate monolith to micro frontends and microservices;

- Migrate to a new design system;

- Setup unit & e2e testing;

- Configure the logging process;

- Setup the deployment pipeline.

In this article we cover the details of the first and last points from the list above, including an overview of the project as a whole.

Project infrastructure: before and after

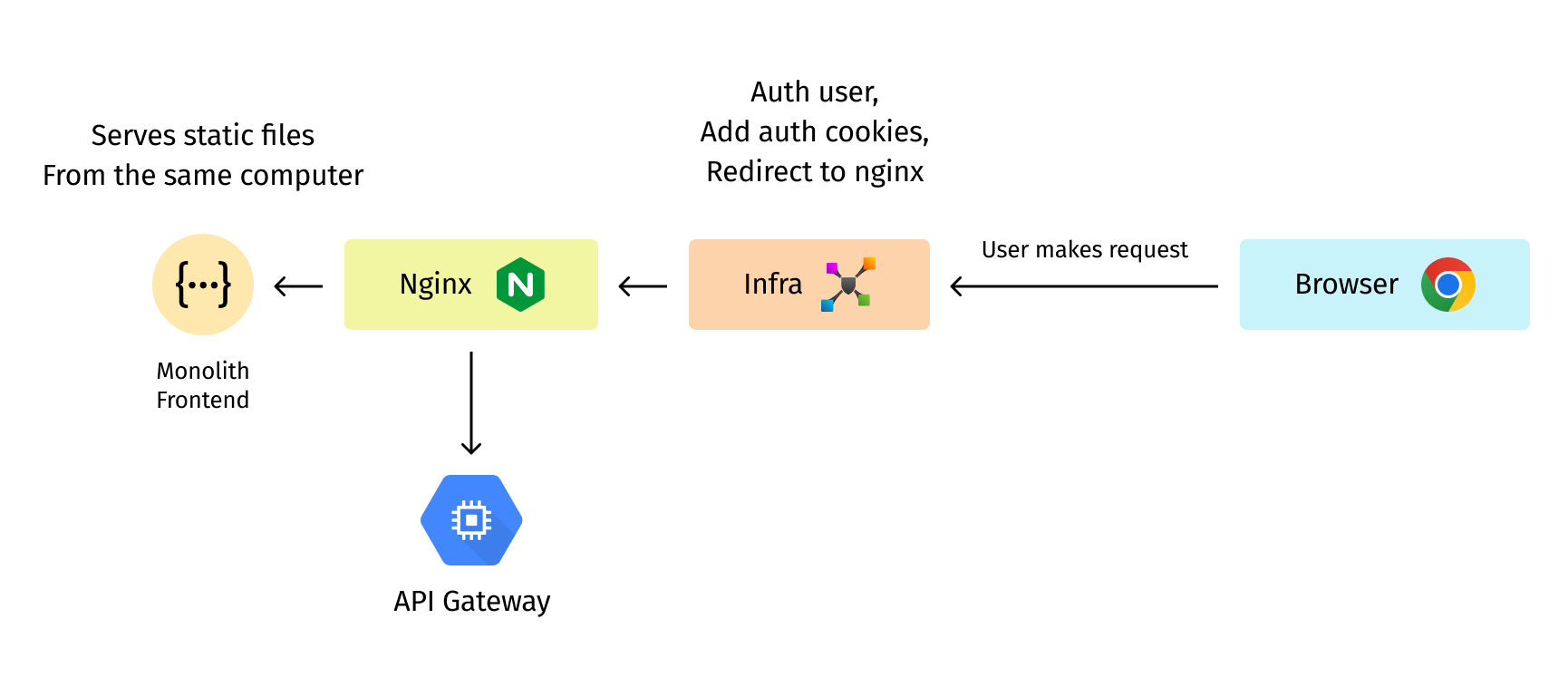

Below is an overview of how the user request workflow was composed before we updated the infrastructure.

The request is sent to the infrastructure that handles authorization, adds cookies and redirects to Nginx, which redirects the request to the required resource or serves static files:

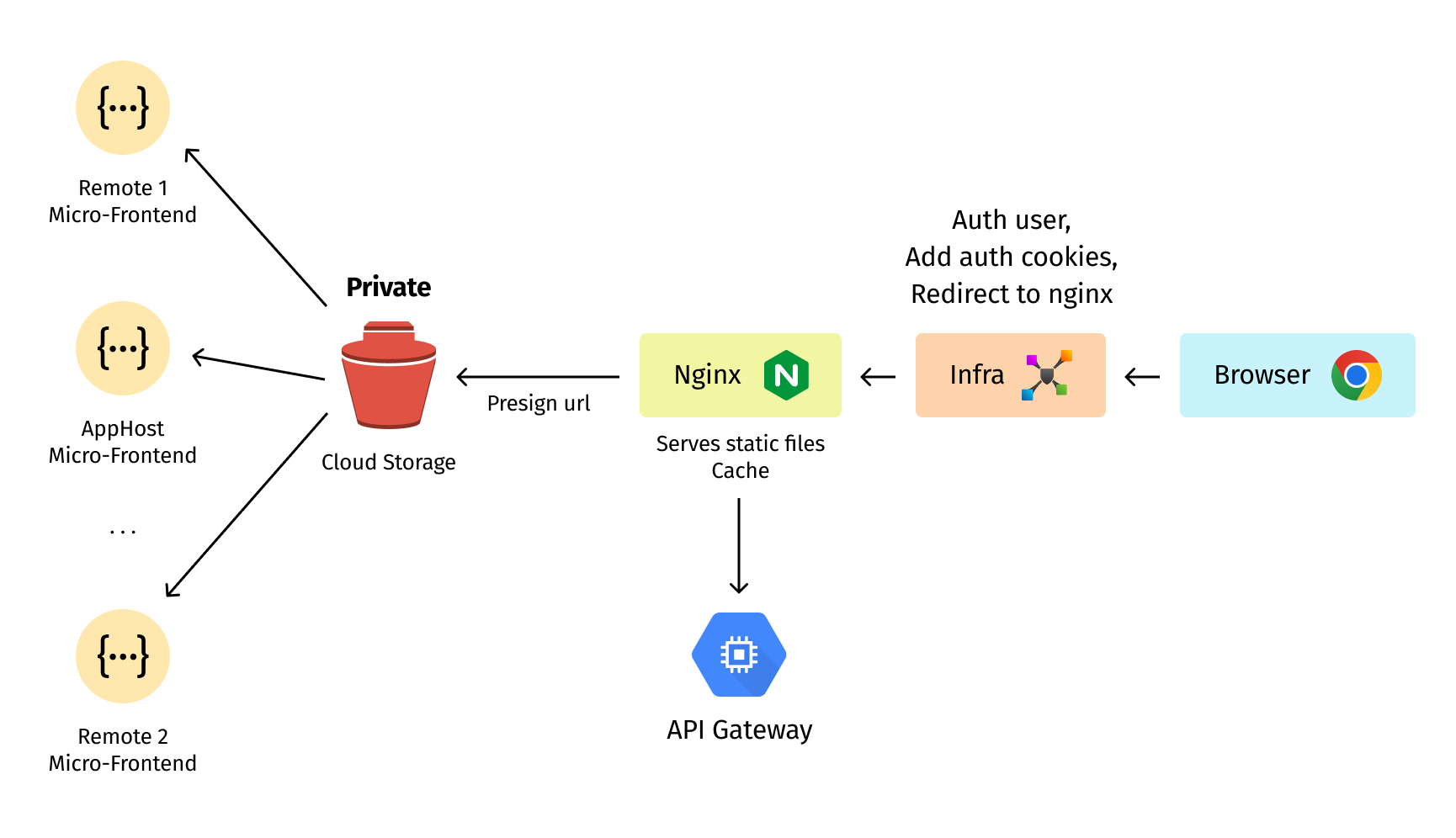

With the new architecture, the request flow is composed as follows:

Amazon S3 is used for static serving, and provides 3 types of storage: private, public and authorized. Nginx is now responsible for signing the url and caching.

What is module federation?

Webpack module federation is a JavaScript architecture invented by Zack Jackson. This architecture enables code and dependencies to be shared between two different application codebases.

The code is loaded dynamically, and where dependencies are missing, they are downloaded by the host application, which reduces code duplication in the application.

Additional motivation to use this approach is the capability to scale apps from mid to large sizes, where scalability is shared among applications at runtime.

Implementation of micro frontend using webpack module federation

Now let’s go through the micro frontends implementation using webpack module federation based on our case:

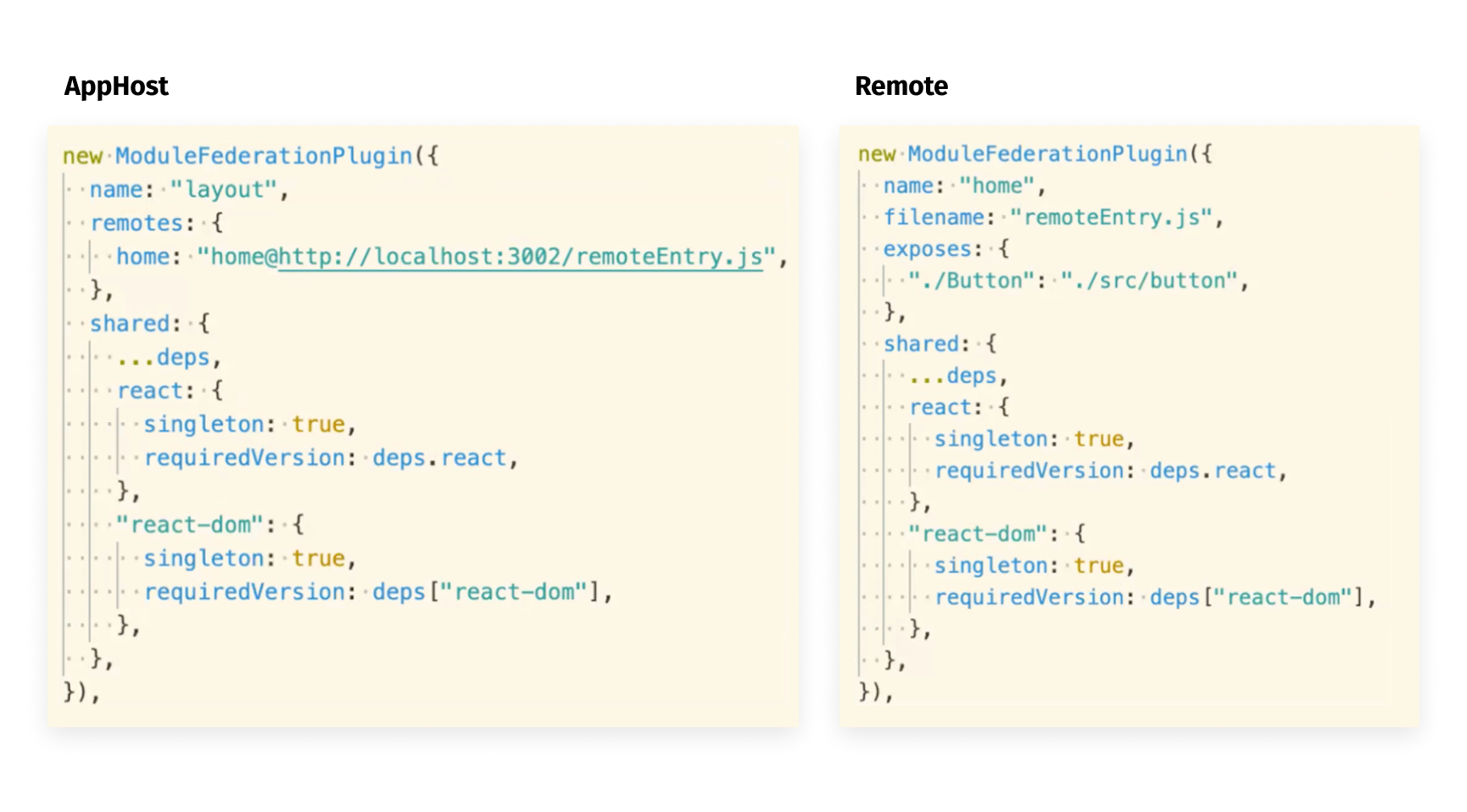

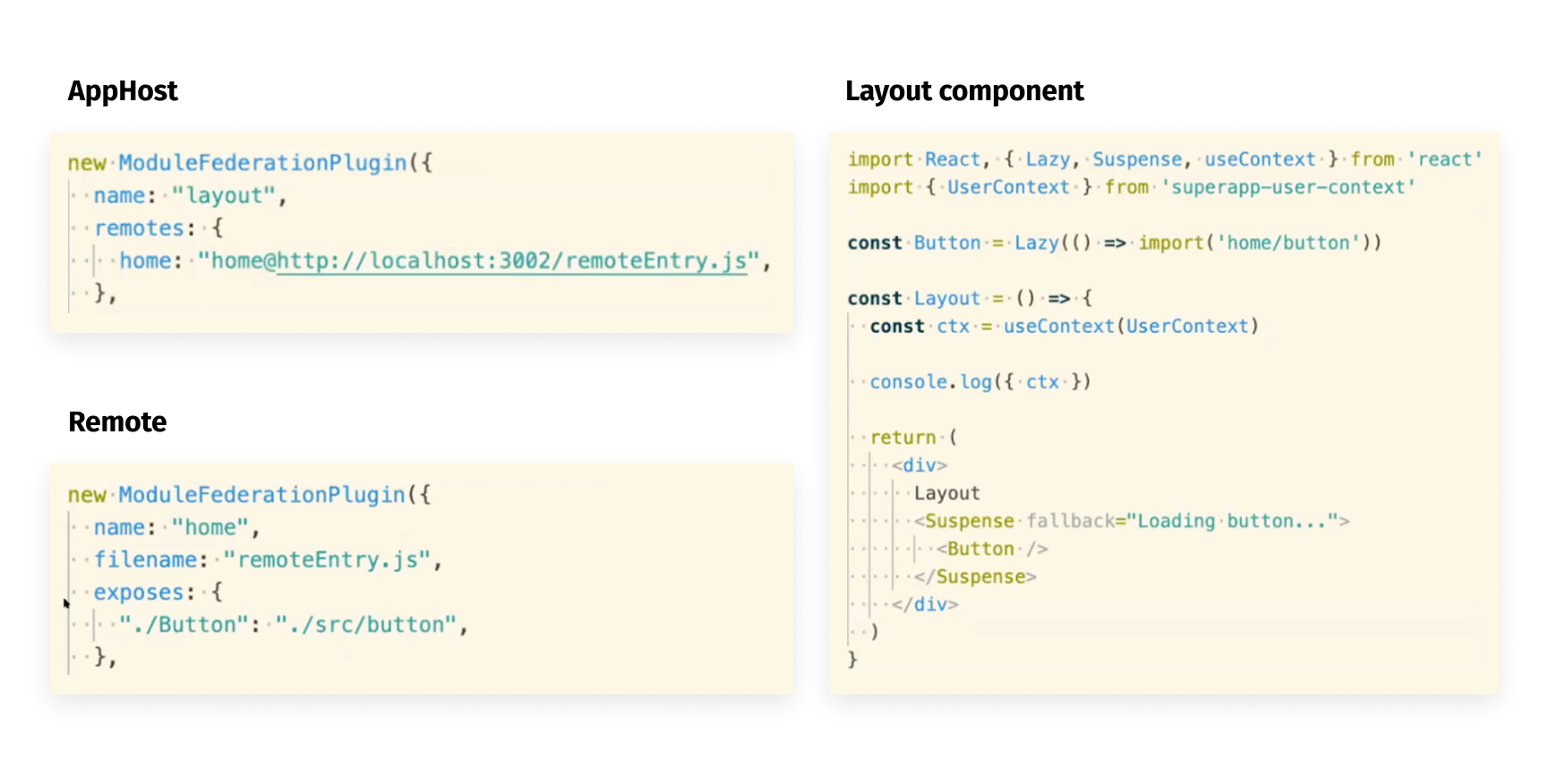

*AppHost is the main application that renders the rest.

*Remote is the element that will be rendered in the AppHost.

All the magic happens in the ‘remotes’ (AppHost file) and ‘exposes’ (Remote host file) fields. Remotes defines a list of urls from where we fetch the code and expose the defined code outside.

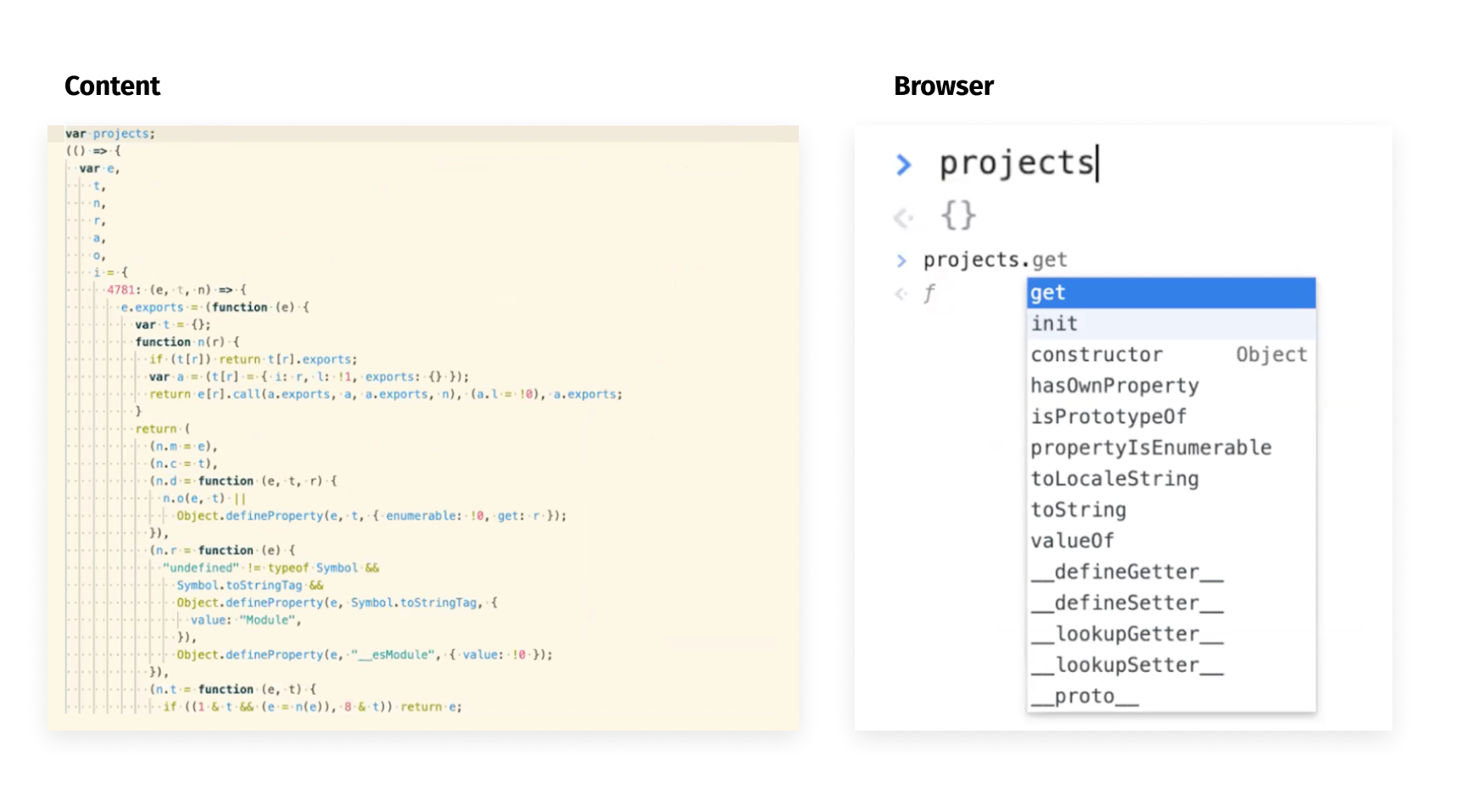

Let’s take a deeper look into the remoteEntry file:

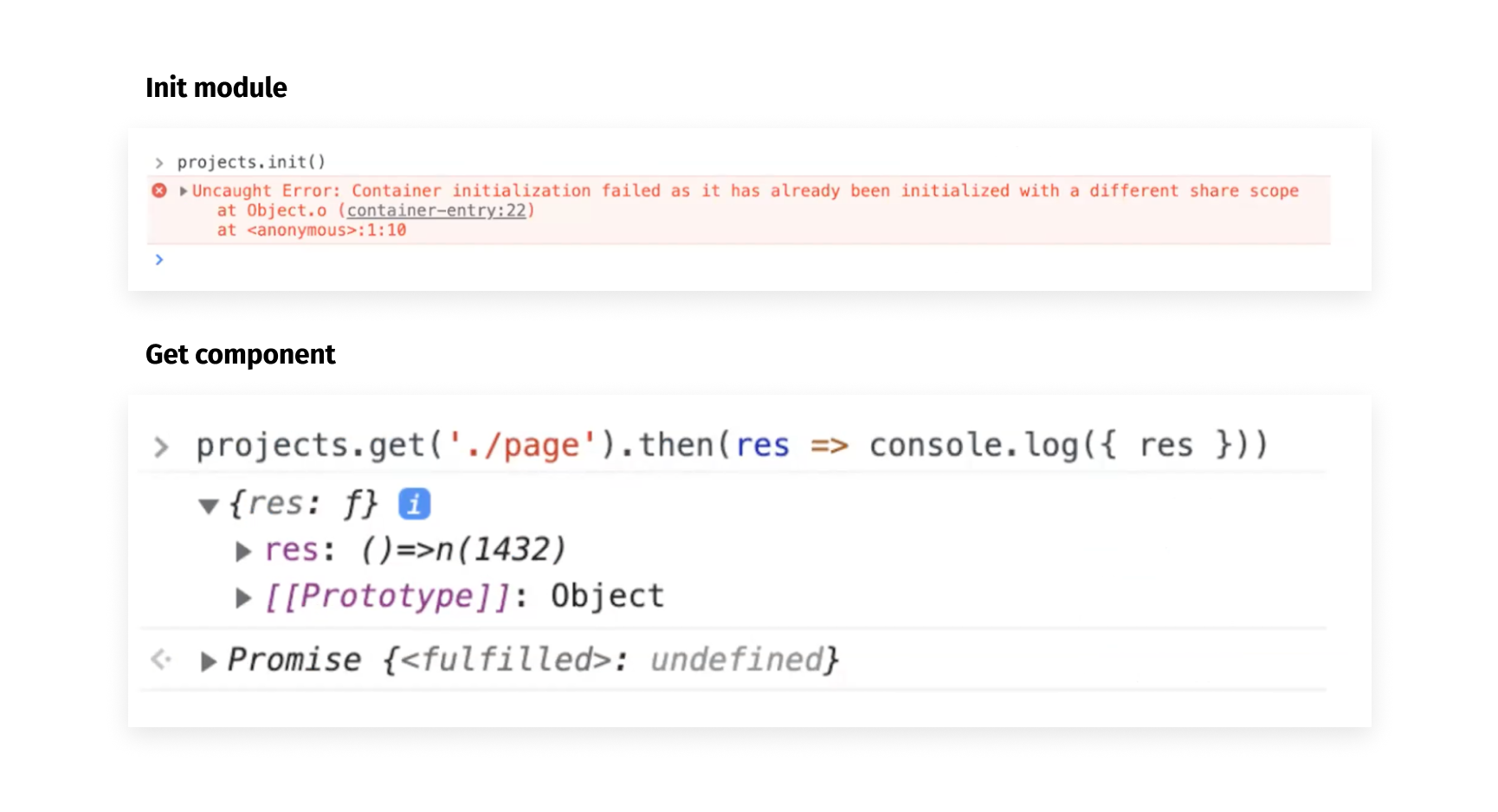

This file starts with defining a name that will be available in the browser as an object with two methods: ‘get’ and ‘init’. As we pass a path into the ‘get’ method, we receive a Promise with chunks of code.

One challenge here is naming of modules, so take a look at the image below to avoid possible pitfalls.

And here is an example of how to use components received from the remote host within an application:

Another challenge was to share context between those components. The solution is depicted below.

Additionally, we need to add the shared context to webpack configuration to enable context usage in remotes.

Deployment

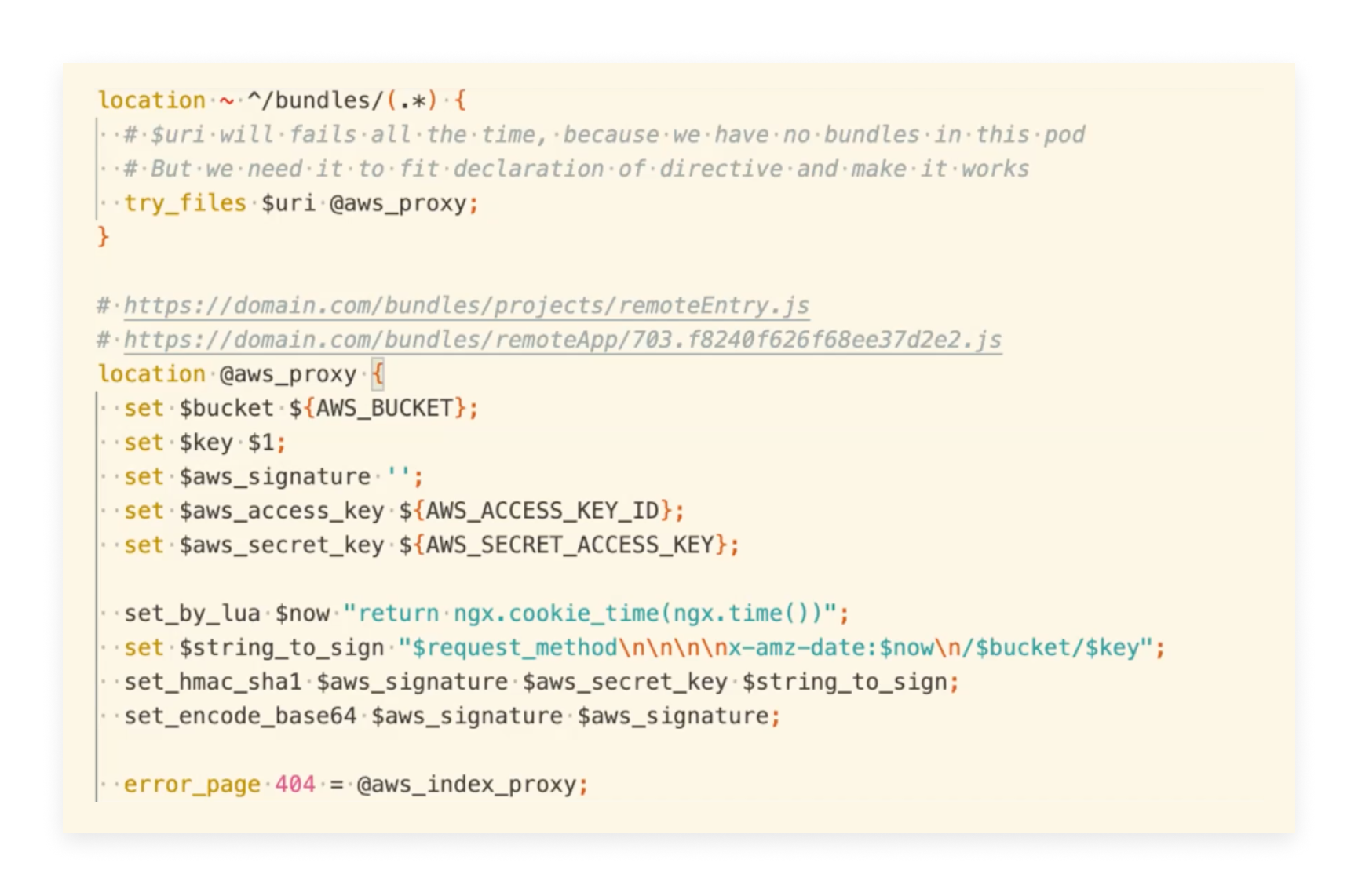

One of the deployment challenges we faced was authorizing the url for Amazon S3. At first we found a third-party service that resolved that issue, but after brainstorming with the team we decided to unload Nginx and do this operation directly on it. You may ask whether it is possible to write code in Nginx, and the answer is - yes, it is possible, but for this you need Lua, a lightweight, high-level, multi-paradigm programming language designed primarily for embedded use in applications:

It’s finally the right time for deployment, right? Not yet.

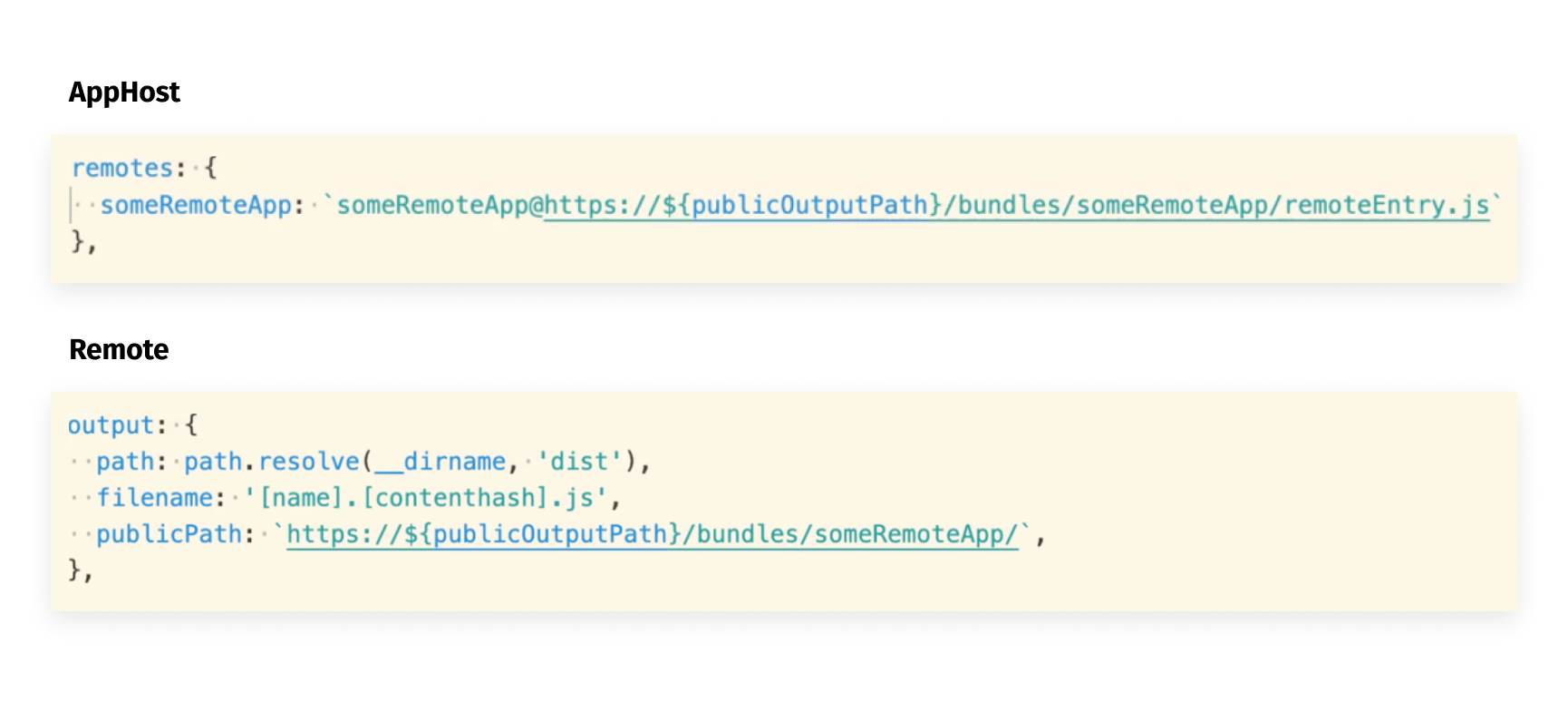

Our infrastructure did not allow us to use different ports, and for this reason, the recommended url declaration method was not quite the right solution. So we decided to handle that with webpack configuration. For development purposes we simply exposed different ports, but for production we created a different webpack configuration, using path to bundle as the url:

Summary

In this blog we have covered: micro frontend architecture, module federation and how to use it with real examples, potential challenges, how to deploy, and strategies for further improvement.

Whether you should or should not adopt micro frontends depends on the size of your project and future growth plans, as this approach is not the best for small applications or businesses. A micro-frontend architectural approach is your best bet when working on a large project with distributed teams to have a fully maintainable and scalable solution to be extended and easily modified.