Smart autocomplete best practices: improve search relevance and sales

Smart autocomplete is an essential feature for improving online catalog navigation and boosting product discovery for users. This is especially true for mobile search, where the smaller screen and keyboard, limit the use of more traditional faceted search selectors. Smart autocomplete, also known as autosuggest, does more than merely forcecast words or phrases the user is typing. Smart autocomplete goes a step further, and anticipates the user’s intentions in order to make helpful suggestions. These suggestions improve the user’s search experience, increasing both online conversion rates and average online cart value.

How smart autocomplete brings value

More than a simple autocomplete or typeahead tool, smart autocomplete can improve the user’s navigation and product discovery experience. Because of its subtlety, the user perceives query suggestions as impartial. This raises its value as a product discovery tool for both users and retailers. Overall, smart autocomplete improves both the customer's experience, as well as helping the retailers merchandisers and bottom line. Here are some of the specific things it can do:

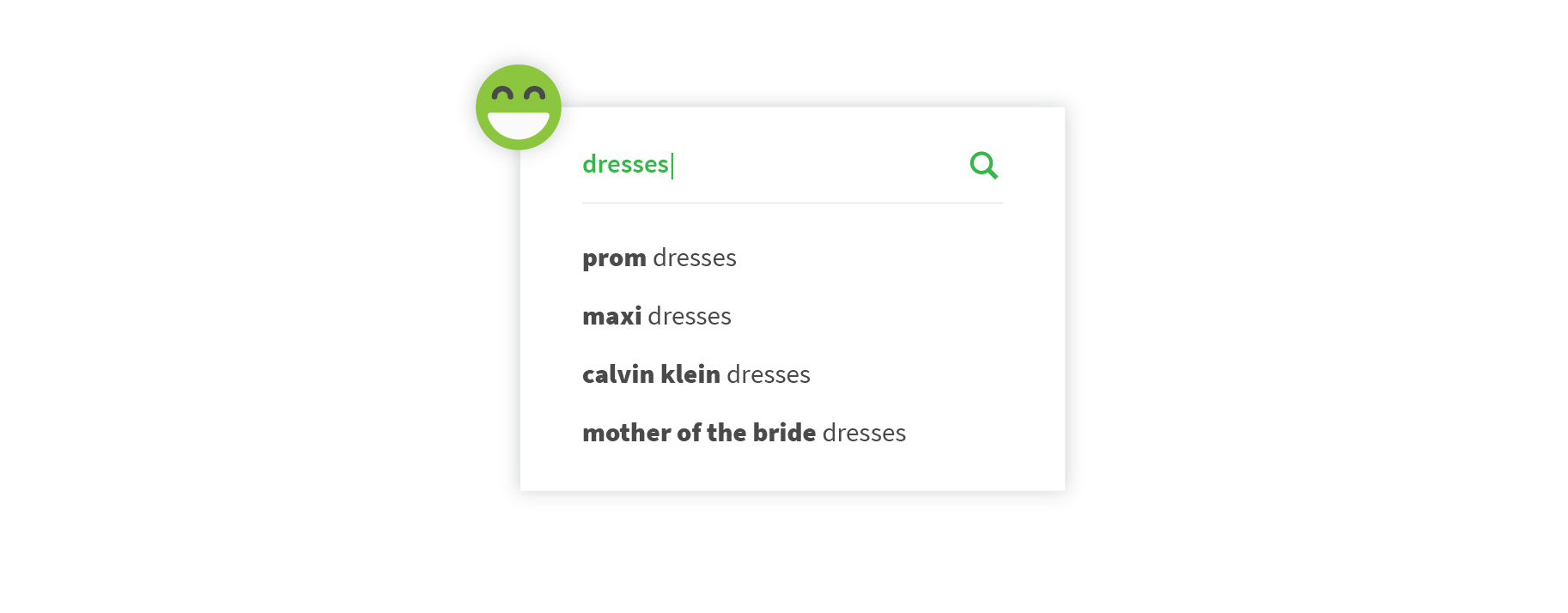

Promotes brands or features from the retailers product catalog

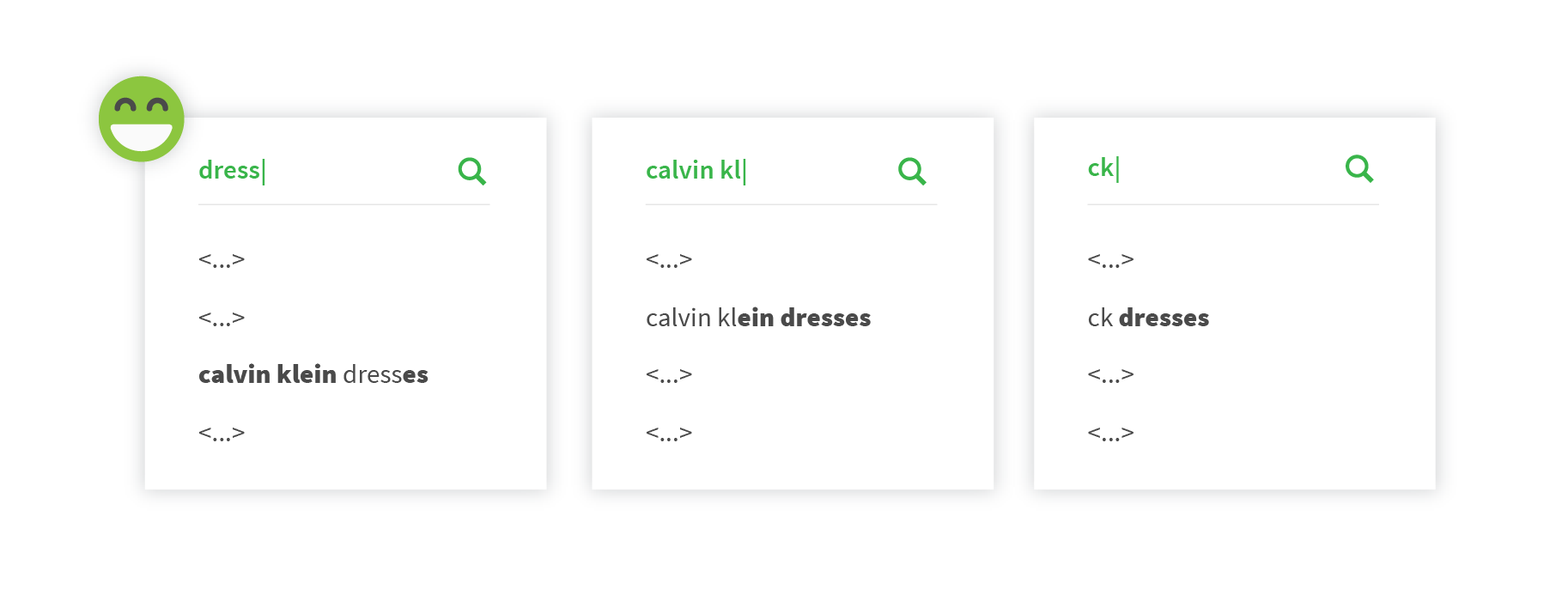

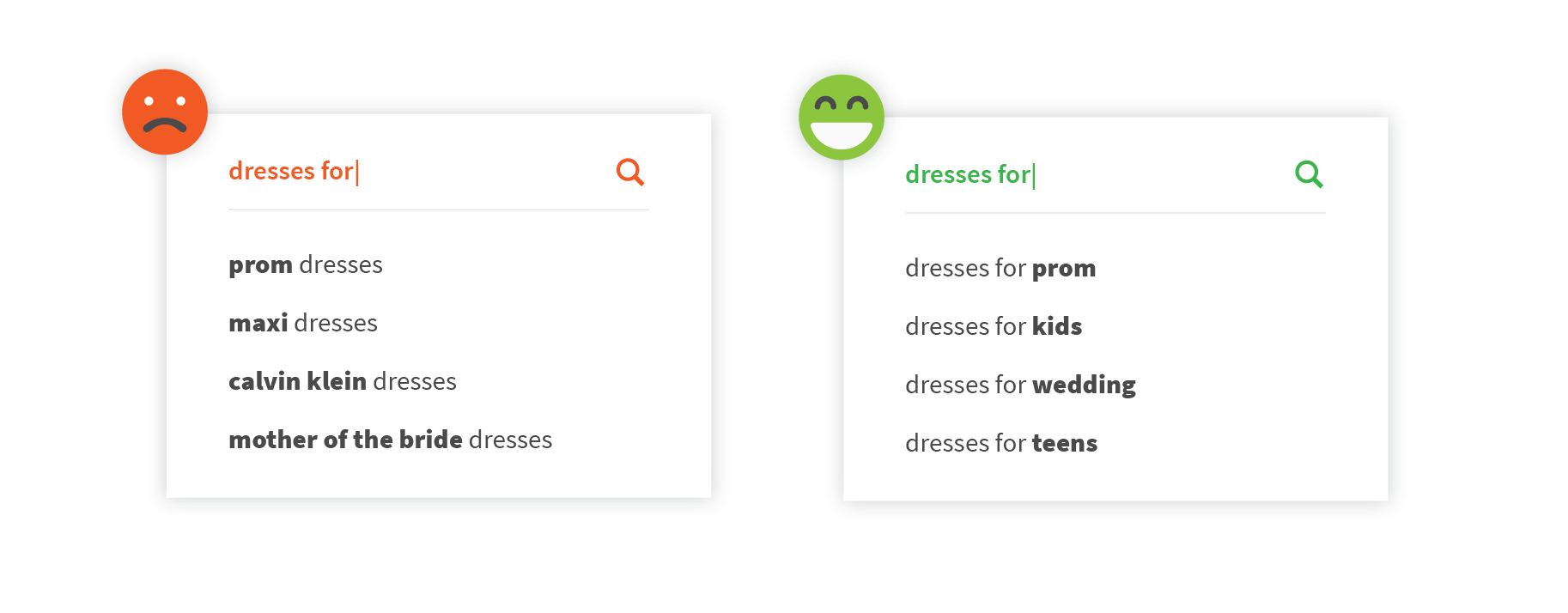

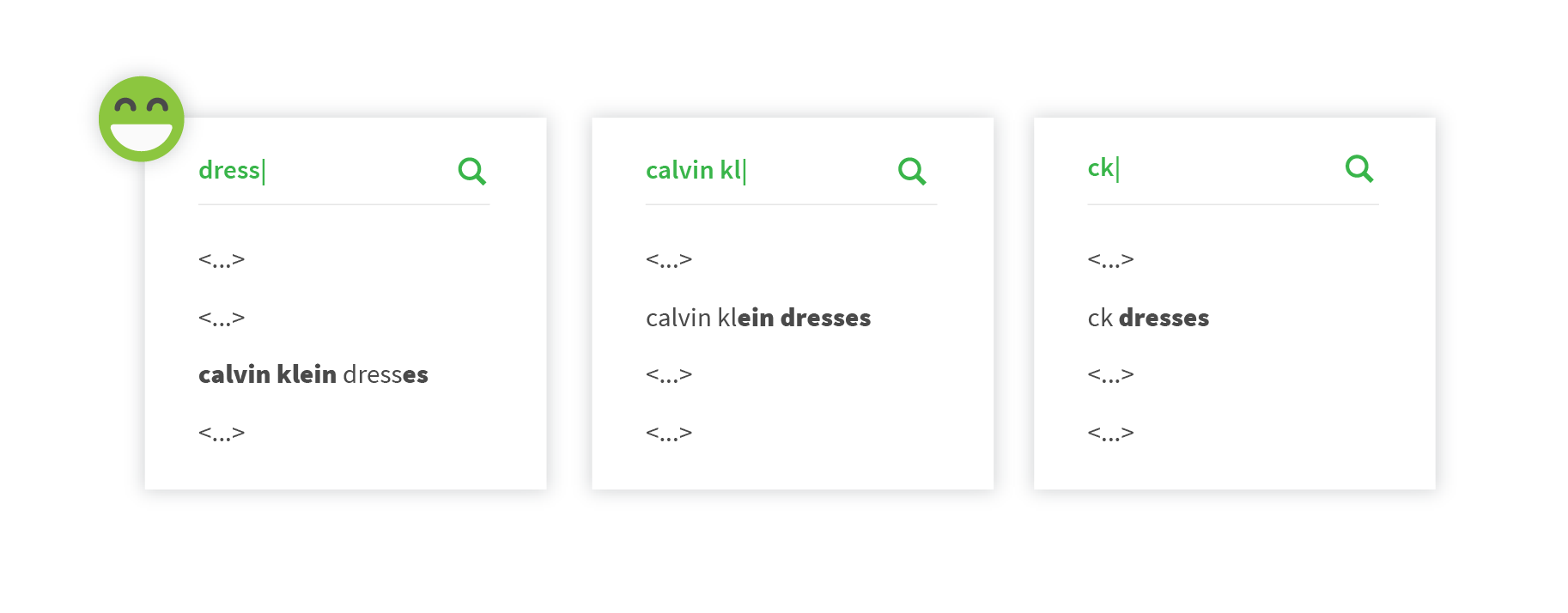

If a user types in a generic subject, say “dresses”, smart autocomplete can use this opportunity to suggest dress brands, like “Calvin Klein dresses”. Smart autocomplete can also suggest dress types, like “prom dresses”, which give users a helpful suggestion, and also applies a merchandiser's business logic of promoting a brand or specific type of dress.

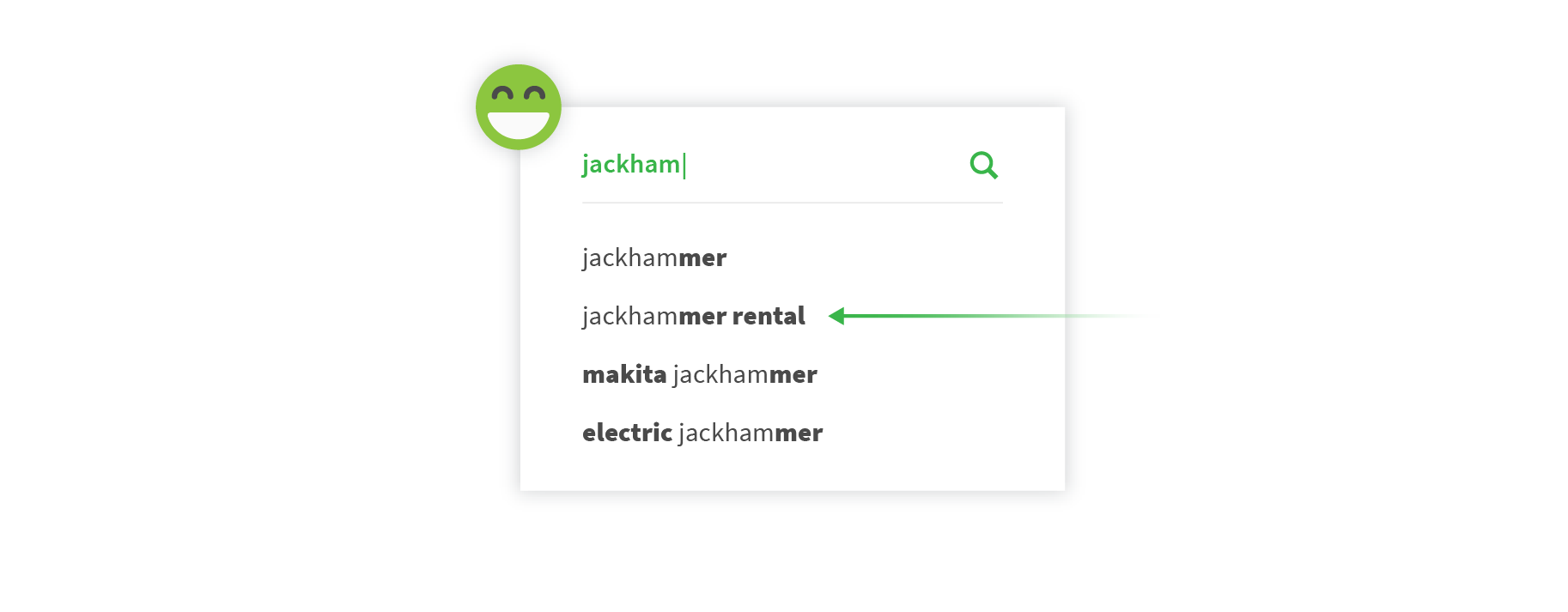

Informs the user of differentiating features

Let’s say a user is searching for jackhammers. This is an opportunity to inform them via the autocomplete list, that jackhammer rentals are also available. This result may appeal to the user who had not even considered this, or was even aware of this option.

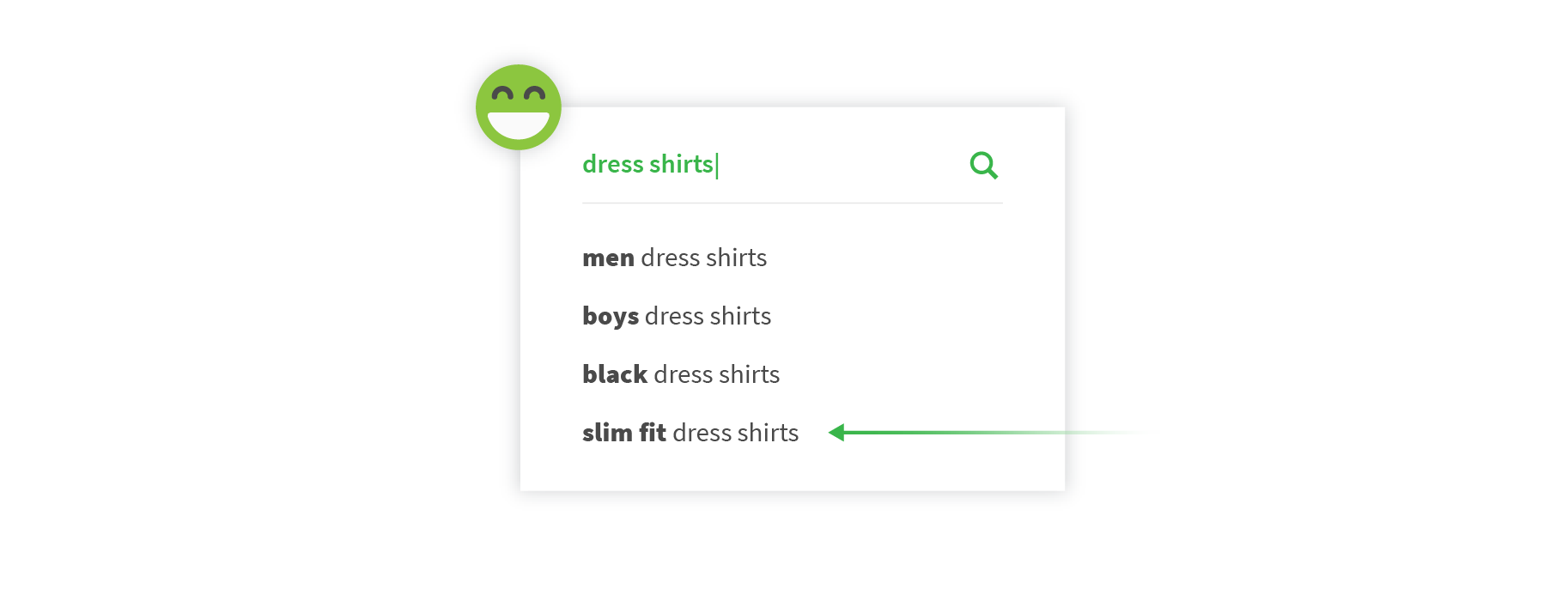

Introduces important product features

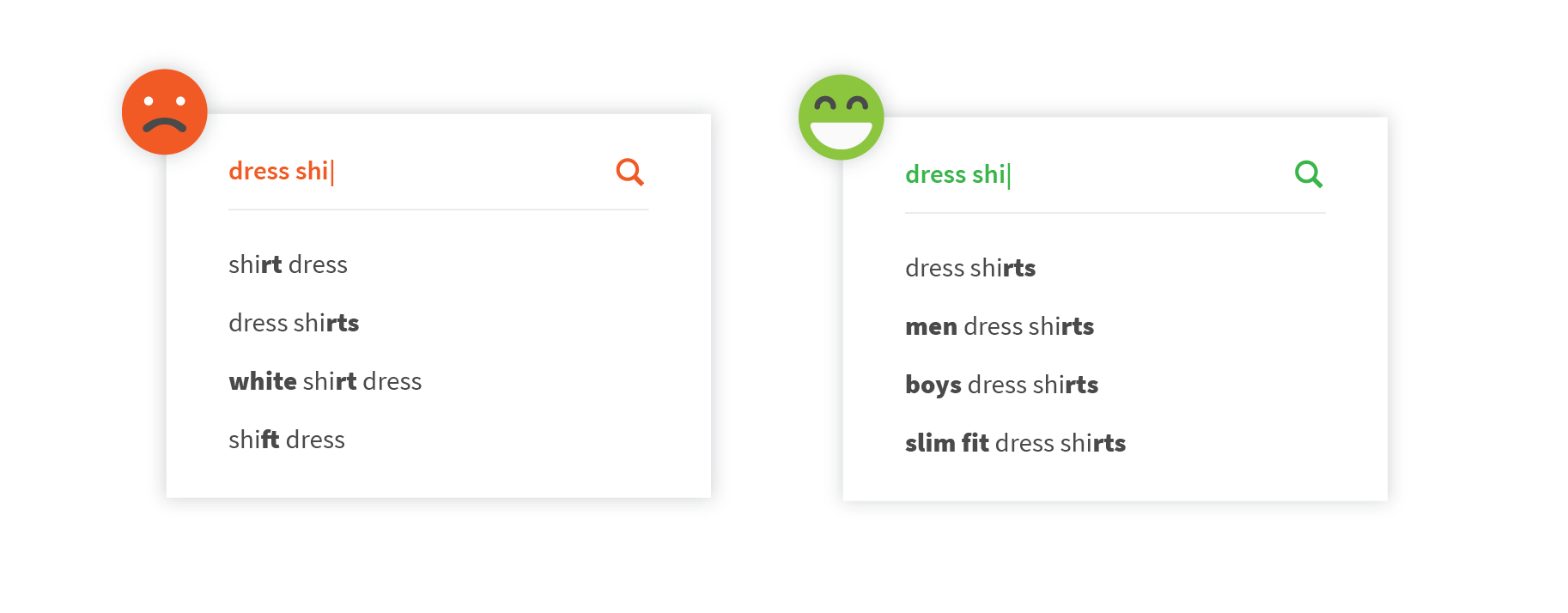

Smart autocomplete can be used to explain or promote important product features to customers. Interestingly, these suggestions are made by other experienced users via their previous search history. For example, users who typed in “dress shirts” might be looking for “slim fit dress shirts”, a suggestion generated by previous users’ searches.

Shows the user phrases supported by the search engine

If a user begins a query by typing “dresses”, autosuggest, supported by the search engine, can suggest “dresses under $100”. In this case, the phrase appears because autosuggest is able to anticipate phrases like "<phrase> under $<price>".

Merchandising through search

Autosuggest can be used for implicitly promoting particular brands without annoying customers with ads and banners. For example, if a user types in “shoes”, and a retailer is promoting the UGG brand, this brand can be placed on the top of the auto suggest list rather than using a banner ad to attract attention.

The quality of the displayed listings covered above are highly dependant on building a quality corpus, the fuel for the autosuggest engine. We will cover how to build the corpus in the next section.

How to build a corpus of autocomplete phrases

Smart autocomplete relies on a phrase corpus, a large and structured set of text phrases, to generate suggestions for user queries. When building a smart autocomplete system, you need to consider two major approaches for building the autocomplete phrase corpus. The first approach, or the customer phase approach, uses customer query data logs to populate the phrase corpus. The product data approach relies on phrases and keywords used in the product catalog. Both approaches have the following pros and cons:

| Approach | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Customer search | ● Natural language ● High recall (incl. synonyms and non-product search) * ● Ranks * (* with high enough volume of search history ) |

● Misspellings ● Semantic similarity ● Irrelevant results ● Zero results ● New product types and brands |

| Product data | ● Correct spelling * ● Relevant results * ● Semantic uniqueness * ● Full coverage of products data (* with correct and consistent products data) |

● Natural language ● Recall issues ● Ranks ● Underused suggestions |

It is interesting to note that the pros and cons of each approach mirror each other. The advantages of one approach often becomes a challenge for the other. However, these two approaches are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, the best approach may be a smart mix of both.

The product data approach can be a good option if the retailer’s catalog attributes are well-defined, and not too diverse. The logic here is that often users are attempting to enter a phrase similar to the one included in the product data corpus, which is based on the product catalog. The product data corpus may also be used simply because data from past customer searches is not available. This may be because policy issues forbid the capturing of consumer data.

The alternative approach uses data from previous customer searches to power helpful suggestions. Given the high volume of searches on heavily trafficked retail sites, this method allows you to leverage popular searches for autocomplete.

When starting to develop a corpus of autocomplete phrases, we recommend initially focusing on customer search phrases. In most cases, the advantages outweigh the challenges. The remainder of this article will focus on the customer data approach.

Building autocomplete phrases from customer searches starts with capturing clickstream data. To build a useful corpus, we will also need:

- A list of search phrases spanning some period of time which produced good recall. Only phrases that were actually typed by the user into the search box or selected in the autocomplete drop-down list should be included. It is required to filter out not only bot requests, but also customer clicks on search URLs, such as banners, and internal or external links. This type of information is excluded because the search phrase in the predefined URL may lack natural language features, but has a high rank, making it visible to the customer. In addition, this URL might be part of a marketing campaign, causing the ranking of autocomplete solution to be biased towards concepts promoted via search URLs

- Clickstream background statistics (number of search events, product views, checkouts)

- Phrase misspelling information. If a user types in a misspelled phrase, collected historical data for misspelled phrases needs to contain the actual corrected phrase, so a match should occur displaying the corrected phrase

- Slicing by context or channel, if required

Once raw clickstream data is captured, filtering will be required to extract useful information for potential autocomplete display results. Any phrase displayed by autocomplete should be relevant to the user. If irrelevant information (false promises) appear in the autocomplete window too often, the user’s confidence in the results will diminish, as will engagement.

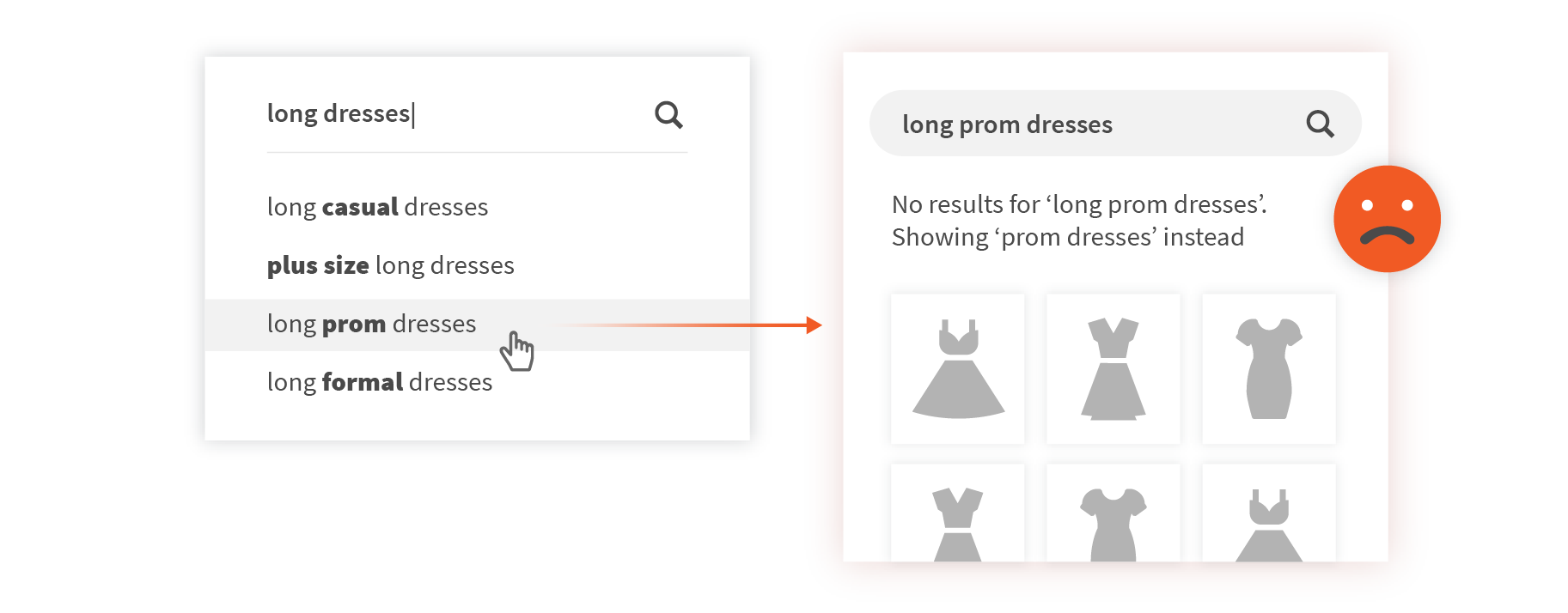

Filtering false promises - partial match

Partially matched phrases which yield a false promise or zero results, should be excluded from the autocomplete display.For example, the query “long dresses” provides the suggestion “long prom dresses”, which has no results but provides a partial match of “prom dresses”. The issue here is that the keyword long has been omitted from the partial match, substantially changing the intent of the original query.

Filtering false promises - exact match

It is possible that an exact match could still yield non-usable items in the autocomplete box.

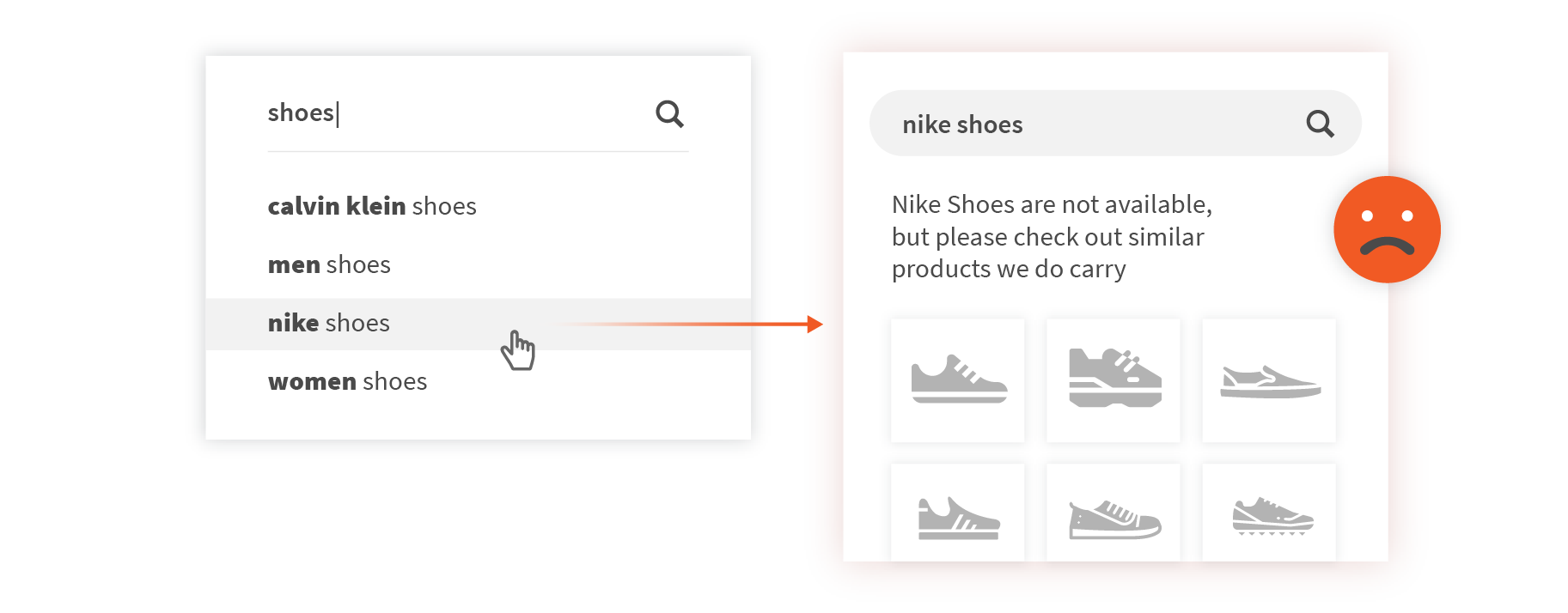

- Phrases triggered by a “do not carry” list which, if clicked by the user, will yield no useful results.

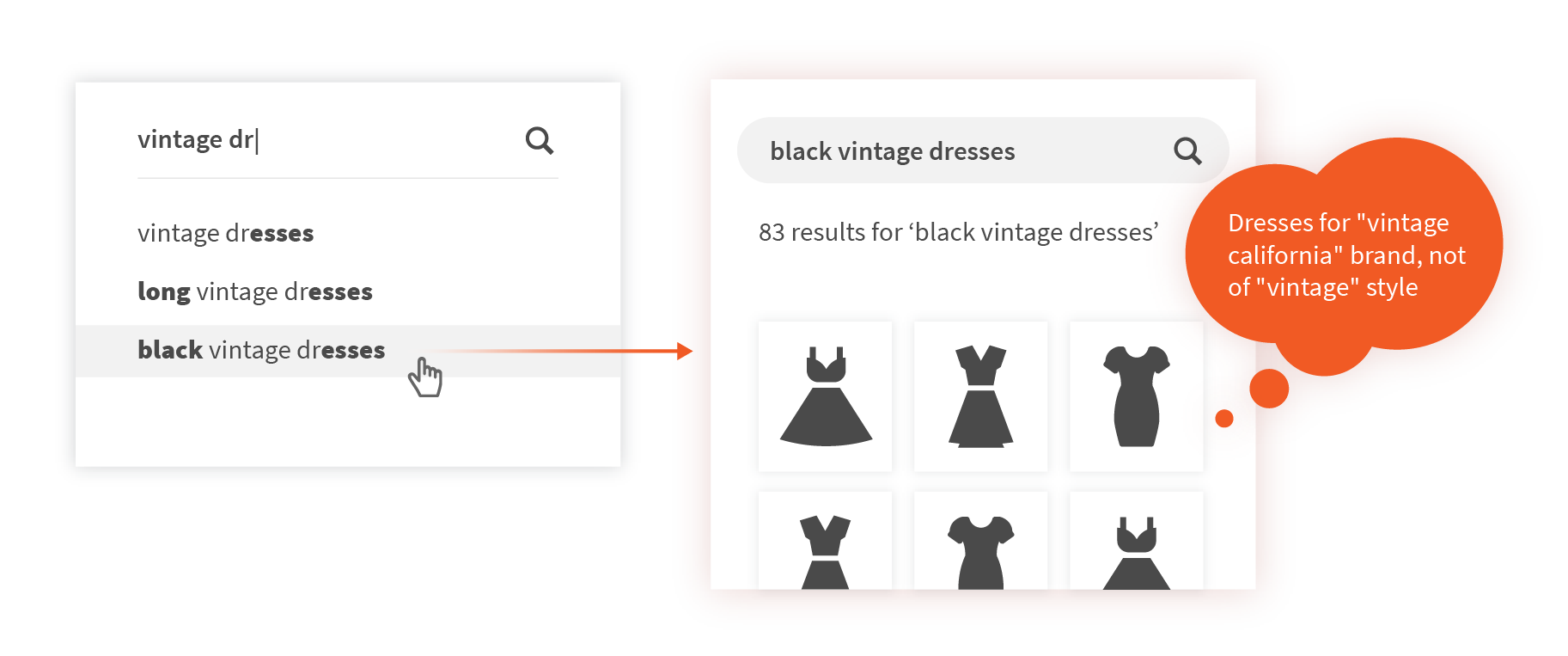

- The words entered by the user may exactly match an autocomplete entry, but the meaning of the words may yield irrelevant results, creating a false promise. In the example below, the word “vintage” could be an adjective describing a type of dress. It can also be a proper noun, as part of the brand name “Vintage California”.

Filtering misspellings

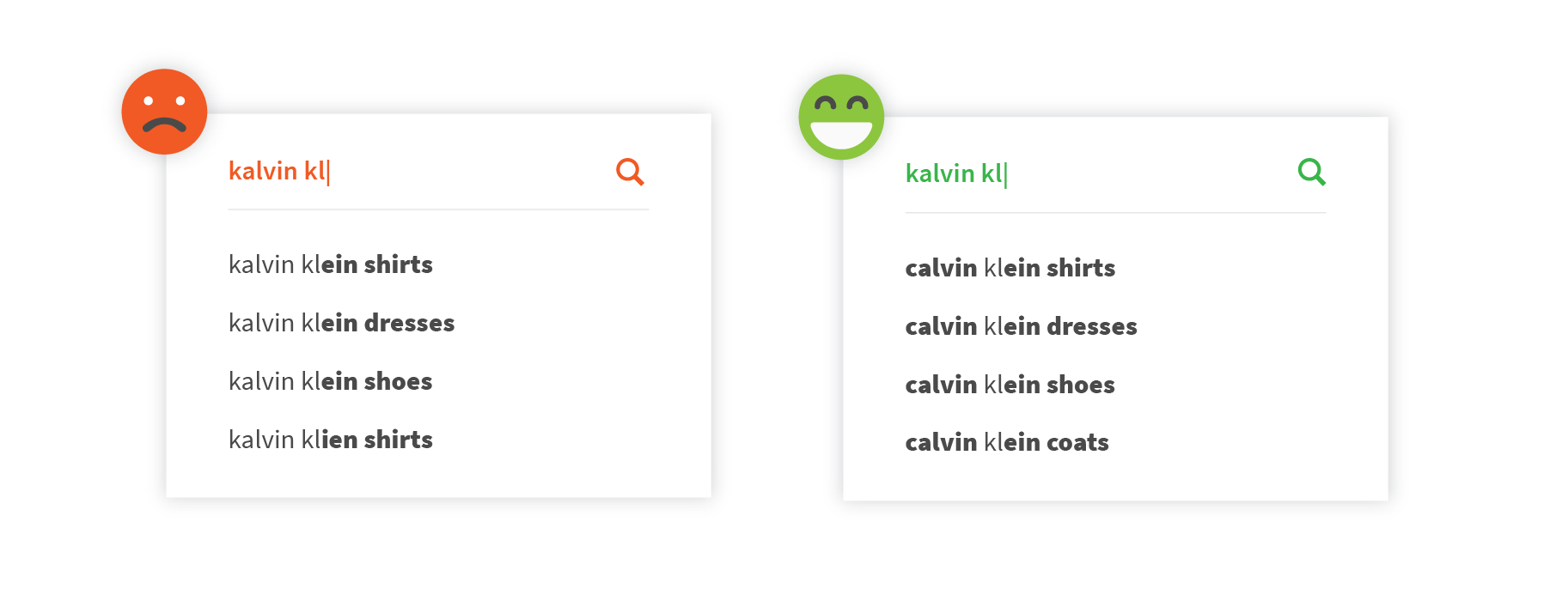

If the search engine supports spell correction at autocomplete query-time, we recommend discarding misspelled candidates for suggested phrases. When a customer misspells a phrase in the search box, autocomplete identifies misspelling, fixes it on the fly and displays the correctly spelled suggestions instead.

Some words, however, are often misspelled, such as “Tommy Hilfiger” or “refrigerator”. These misspelled phrases can represent a significant amount of traffic. In these cases, discarding misspelled phrases will bias the ranking towards the terms with easier spelling. To avoid this, business metrics of misspelled phrases should be inherited by phrases with the correct spelling.

Additional difficulties can be introduced by misspellings in the retailer’s catalog data. For example, it is possible to find difficult words such as “fuchsia” or “fluorescent” spelled incorrectly, even in product catalogs. Unfortunately, this issue affects not only autocomplete, but also the core spell correction functionality. The best solution is to carefully QA the product catalog data.

Semantic deduplication

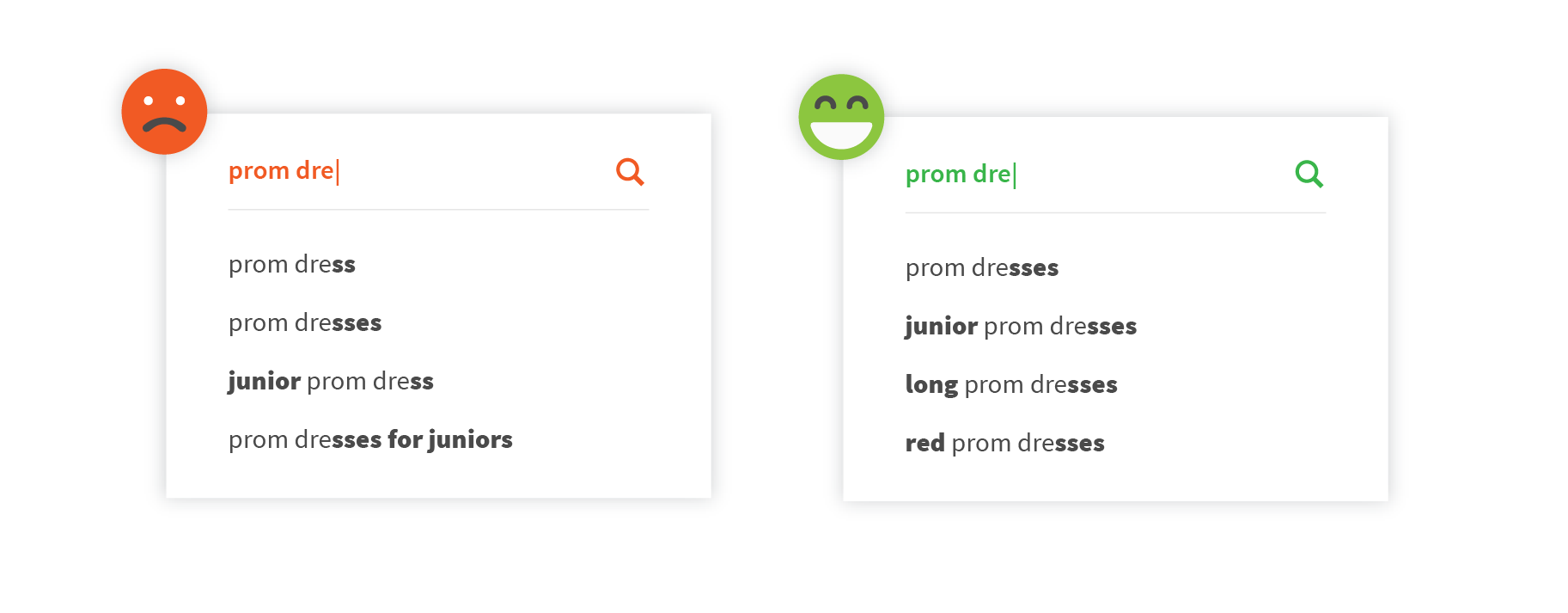

Phrases which are semantically similar but contain different spellings should only be displayed once. For example, the word “dress” and “dresses” are semantically similar, but the difference is, one is plural. Only one form should appear in the autocomplete window.

Semantic deduplication - close spelling

Autocomplete must not show semantically identical phrases with close spellings, for example:

- Singular vs. plural forms of nouns (“women dress” vs. “women dresses”)

- Order of words (“long blue dress” vs. “blue long dress”)

- Compound words (“dishwasher” vs. “dish washer”)

- With and without stop-words (“women dress” vs. “dress for women”)

- Special characters (“swell bottle” vs. “s’well bottle”)

- Alternative spellings (“barbecue” vs. “barbeque”)

Semantic deduplication can be achieved by normalizing phrases to exclude all “semanticless” features. There can be exceptions for this approach (like “shirt dress” vs. “dress shirt”), which have closed spelling, but different semantics. This normalization can only be used for deduplication, not for a display list.

Semantic deduplication - different spelling

There can be semantic similarities between phrases with different spellings. This type of duplication, however, may not be noticeable, except to users with a deeper knowledge of the business domain.

For example, phrases with different spelling, but with the same semantics due to synonyms, could be treated as the same item. A full phrase could be treated the same as an abbreviated phrase. “Calvin Klein dress” is the same as “ck dress”. Product type synonyms can also be treated the same. An example of this rule is “living room sofas” verses “living room couches”.

Phrases with different search terms, but yielding the same results may also not be noticed except by a user familiar with the product. For example, “Lancome” and “Lancome Cosmetics” could be considered a duplicate.

Semantic deduplication - processing of semantic groups

Phrases from a semantic group may satisfy all other criteria of filtering, we recommend keeping them all in the corpus. This will ensure good recall even for those queries which match only one phrase in a group. However, the phrases should be marked by the same label within a semantic group. Therefore, if a query matches any phrase in that group, autocomplete will display only one instance in the display list.

Other filtering

It is possible that some poorly spelled phrases will pass all through all filters, therefore it may be required to add additional rule-based filters to block unwanted phrases from the user:

- Filter phrases by popularity. Unpopular phrases are more likely to contain some malformed language, even if the words in the phrase are all spelled correctly.

- Some phrases may be suppressed via blacklist, which can be triggered in both “Exact Match” as well as “Contains” modes. A blacklist can be used to filter out inappropriate phrases.

- Additional basic filters by phrase contents (length in characters, length in tokens, undesired special characters, etc.) can be used to filter out malformed phrases, which somehow passed the popularity threshold. However, it is not necessary to identify all variations of malformed phrases. If a malformed phrase is accepted as a valid suggestion, it is rarely displayed to a customer, as it is likely to have a low rank in the semantic group.

Using autosuggest techniques to generate business reports

The process of filtering and grouping customer phrases for use with autosuggest is similar to other processes such as generating business reports on customer search habits. In fact, this reporting can become useful in many other business cases going beyond autocomplete. It can help retailers get a deeper understanding of how customers interact with the search engine.

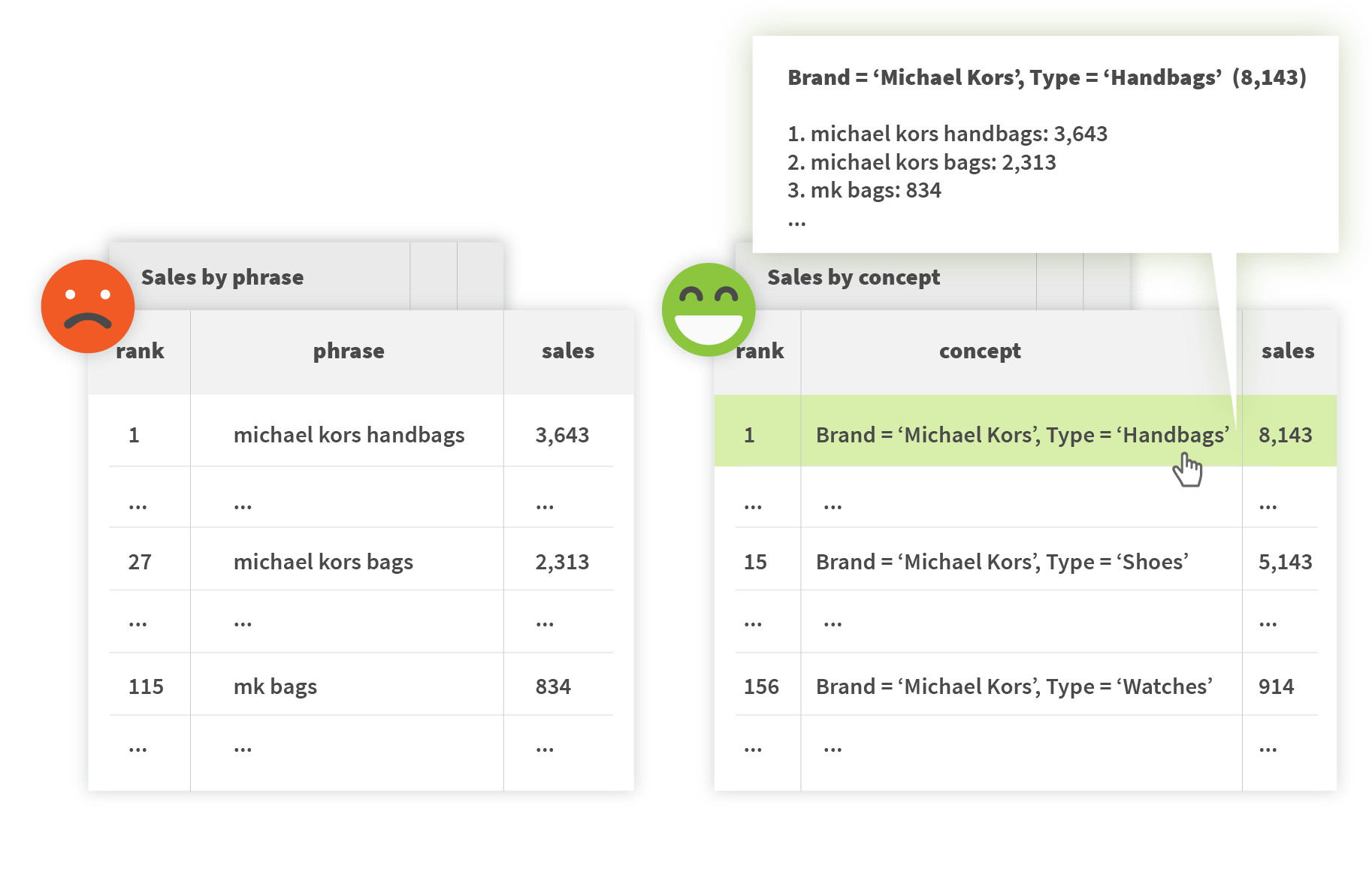

Analysing business metrics

Grouping similar semantic concepts is useful for extracting sales and conversion metrics. In the example below, separating “Michael Kors handbags”, “Michael Kors bags” and “mk bags” is not useful for reporting purposes. Autosuggest filtering can collapse these entries into one entry with a similar semantic concept. This revised list produces a much more useful report.

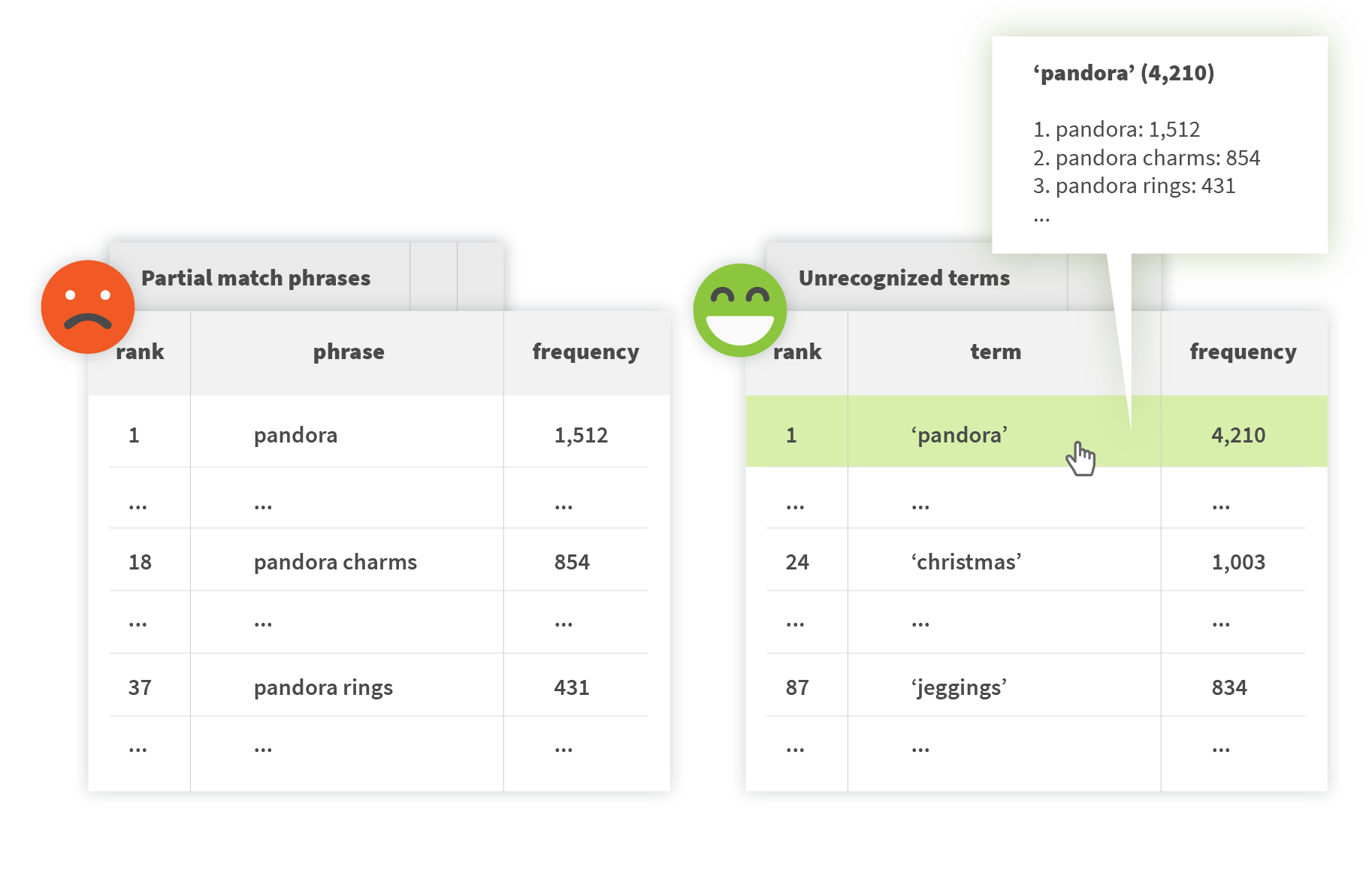

Analysing partial match phrases

Partial matches may contain a relevant key match mixed with unrecognized terms. This type of report capture and emphasize this type of information. In the example below, “Pandora” is a brand name. Grouping all phrases containing "Pandora" gives insight to the number of times a user search for this brand, regardless of additional information they provided in the search bar.

Analysing customer misspellings

Common misspelled terms should analysed, as it may contain useful information for potential sales conversions. For example, a user might type “Ridgid”, a brand of tool this retailer does not carry, but which have close spellings to words existing in the index, like “rigid”. This would create a false positive, and should be blocked by the spell corrector module configuration if it occurs too often.

Common misspellings should be captured along with properly spelled phrases for reporting purposes.

Analysing exact match phrases

As with autosuggest, exact match phrases producing false promises may produce a dissatisfied customer. This information can be useful to companies looking to raise customer satisfaction.

Building a high quality text corpus is important, but only part of the autosuggest equation. Query-time matching and ranking must also be considered to produce the desired results. We will cover query-time operations next.

How to match an input query on a phrase suggestion

Conservative normalization

It can be tempting to use typical normalization techniques from traditional product search with autocorrect search, but this may have undesirable results. An autocomplete input query attempts to match as the user is typing. The incomplete phrase is often small, and we need to consider every aspect of it. This can be lost if significant normalization is applied. Therefore, we will apply what we call “consertative normalization”.

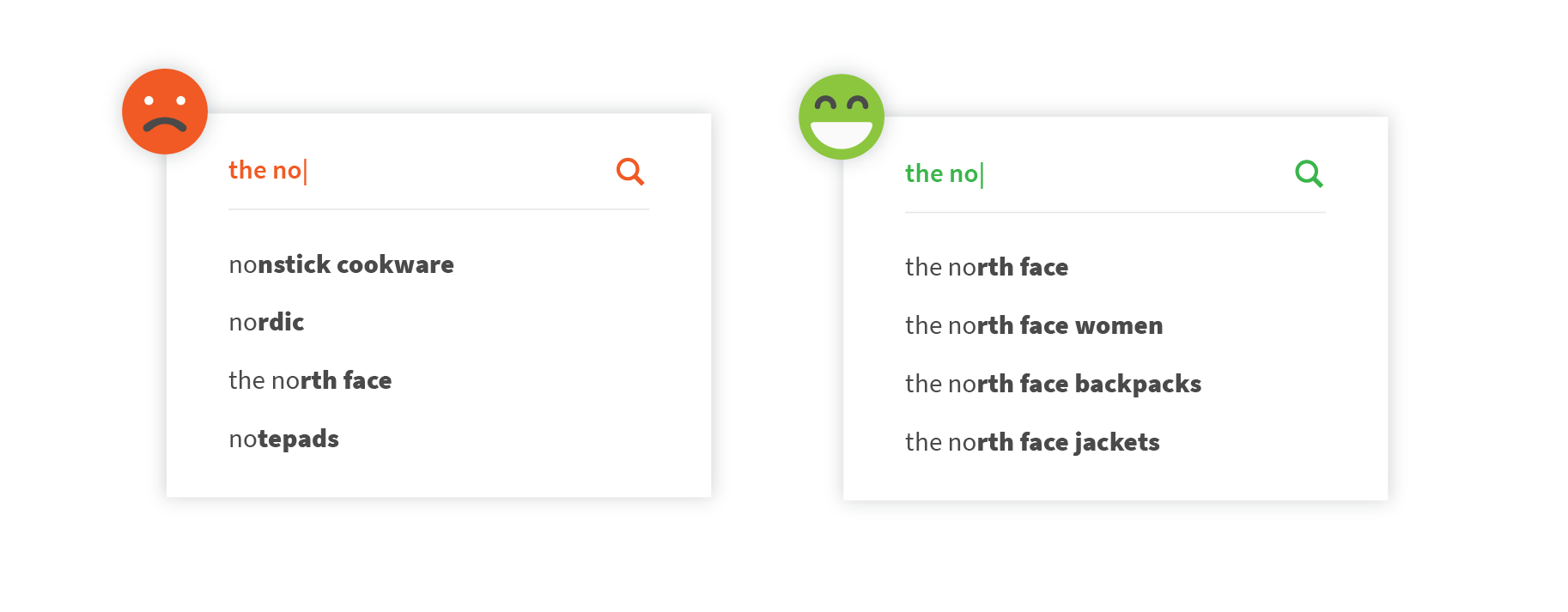

Conservative normalization - preserving stop words

There are instances when preserving stop words, words a search engine will typically ignore, can be useful. Stop words can be the part of the brand name, such as “The North Face”. In this case, when the query is “the no” , “the” should be preserved since it can help to identify customer interest in The North Face products sooner.

Stop words also can add more meaning to the sentence phrase structure. This additional information may make the typeahead prediction more accurate.

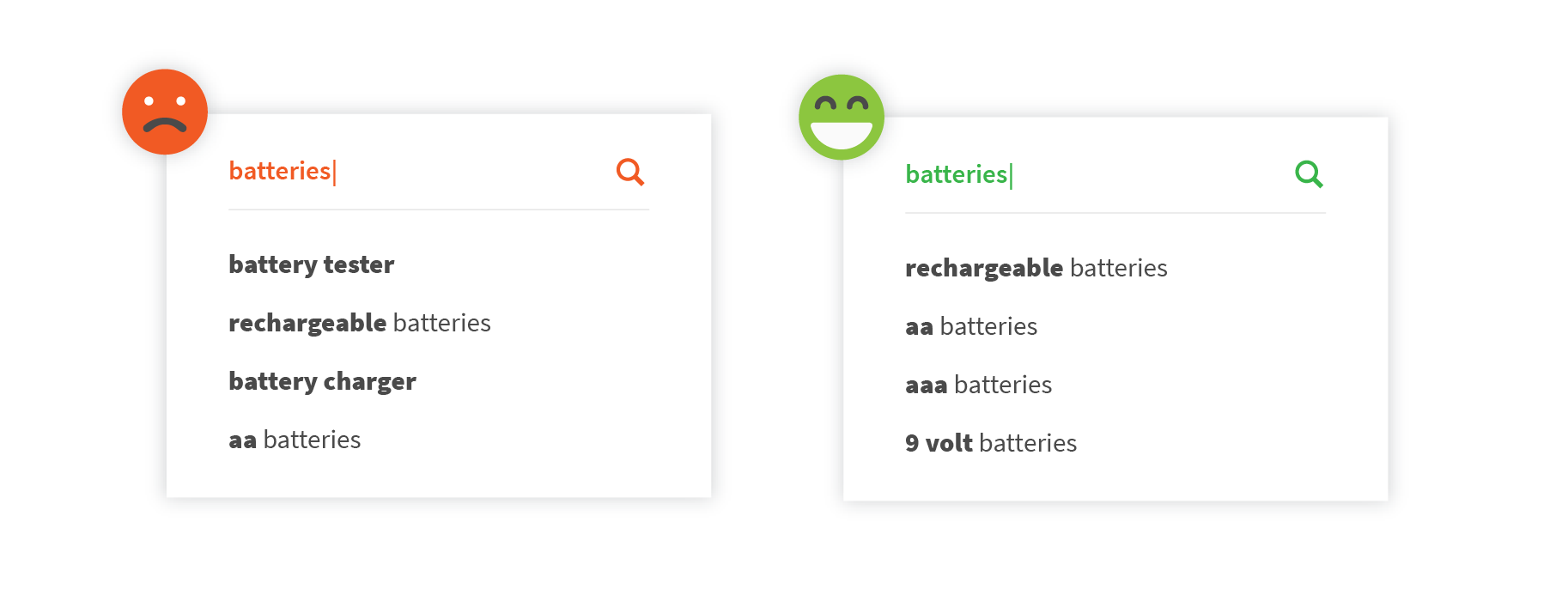

Conservative normalization - do not apply stemming

Stemming, the process of removing a word stem suffix to reduce it to its root form, may alter the intent of the customer query. For example, a word like “batteries” is typically used as a noun in its plural form. If it is stemmed to its singular form, “battery”, this could introduce unwanted matches to its adjectives form, such as “battery charger”.

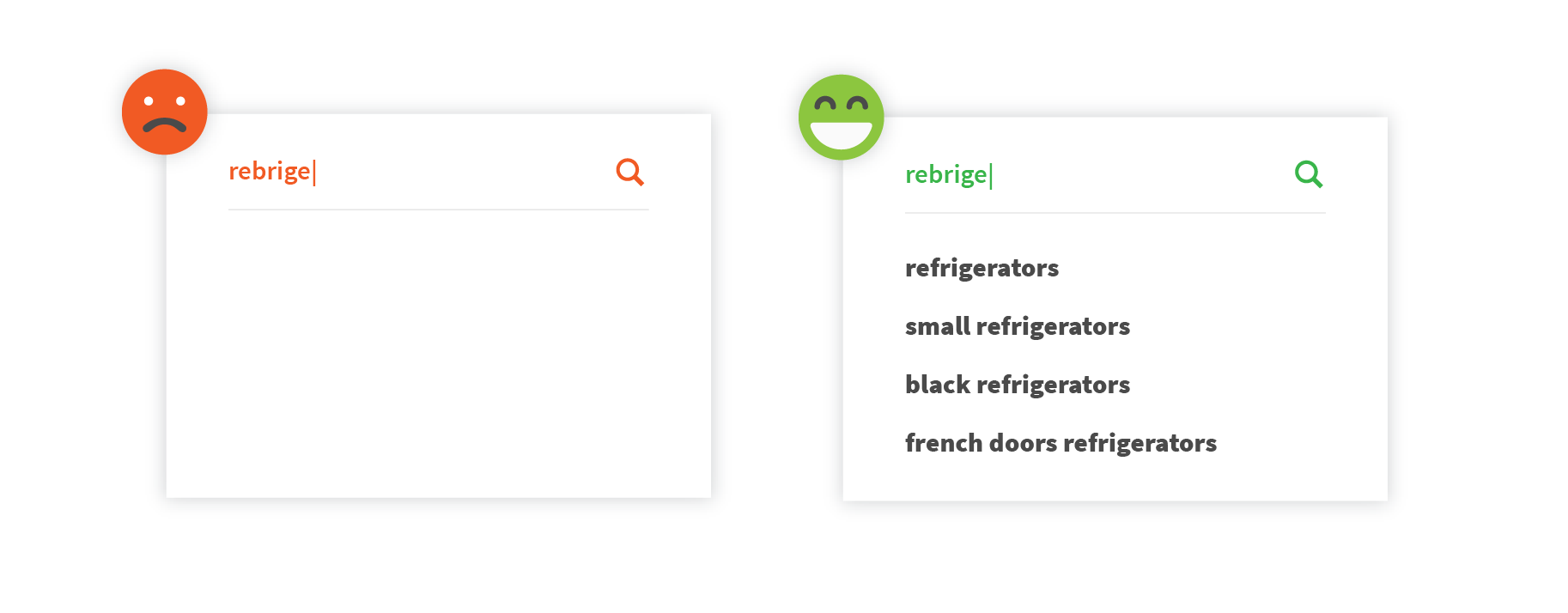

Conservative normalization - spelling correction

Query-time spelling correction is considered a good practice, because the user can immediately see feedback of the correct spelling. Spelling correction and matching should be attempted, as the user is typing, rather than waiting until the user completes the potentially misspelled word, as shown in the example below.

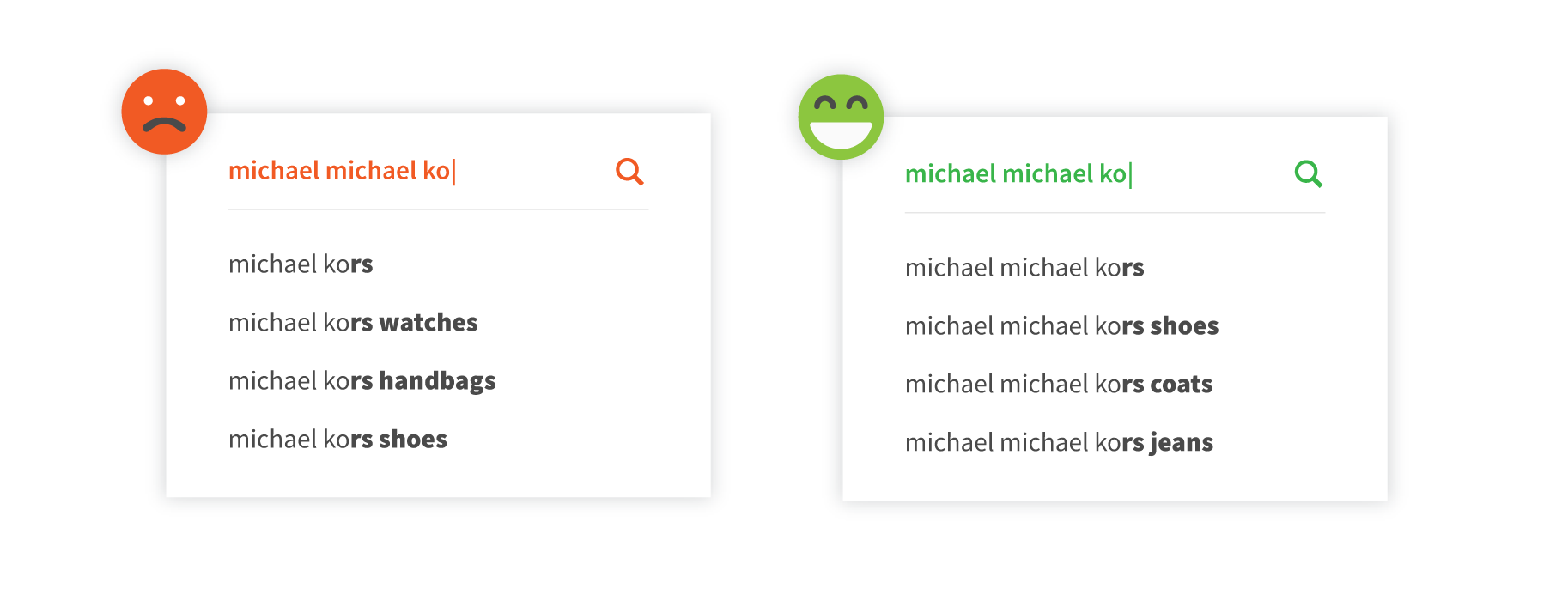

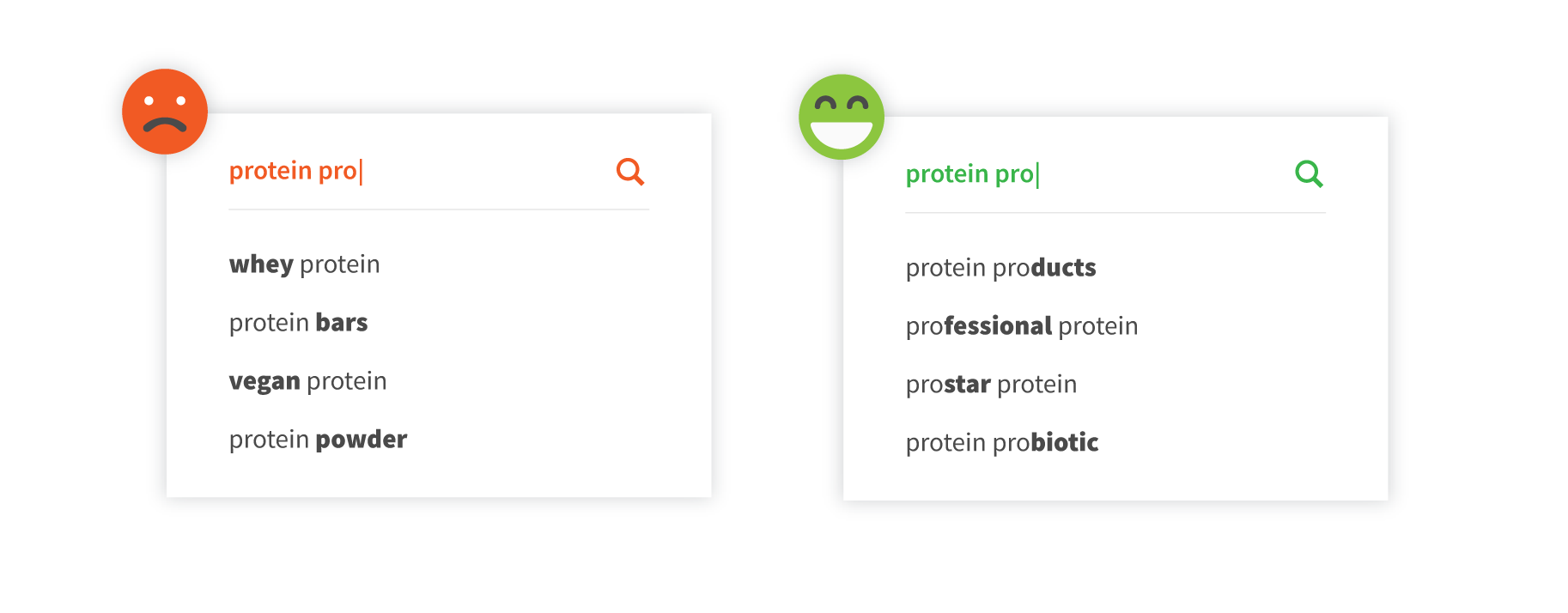

Conservative normalization - multi-match

Multi-match is used in product searches to allow matching of different tokens of a phrase on the same product attribute or value. For example, it can help query tokens with different kinds of spelling to match the same product value through synonyms, such as "black oxford shoes".

We don’t use synonyms for autocomplete during query, and we do not need multi-match at query time. Every token of the query has to match its own unique token in an autocomplete suggest phrase. This helps identify cases when a repeated word changes semantics. An example of this is Michael Michael Kors, which is a sub-brand of Michael Kors.

The absence of multi-match is also helpful when the last incomplete query token (for example, in the figure below, “pro”) and a complete query token (for example, “protein”) are accidentally able to match the same suggest phrase token.

Semantic deduplication at query-time

After building the phrase corpus, semantic deduplication should be applied at query-time. If semantically similar phrases have been marked with a shared label during the corpus building process as suggested, these labels can be used to deduplicate during query time. Only one phrase with the same label should be displayed.

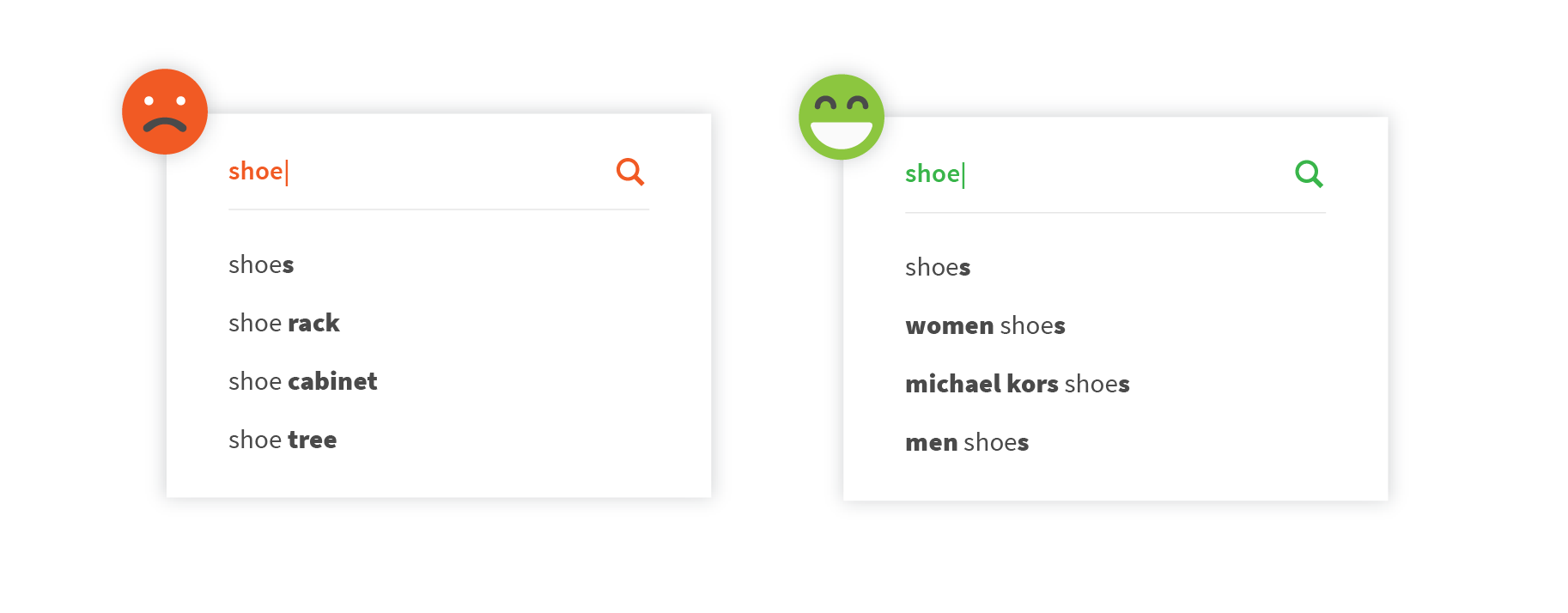

Matching logic

If smart autocomplete is only used as a typeahead feature, it can be tempting to allow the match only from the beginning of a suggestion phrase, like matching “shoe rack” for “shoe”, but not “women shoes”, but this simplistic approach should not be used. Users increasingly use the search bar for interactive suggestions, which can be accommodated by smart autocomplete:

- A user types a product type (like “shoes”) to see what options are available and were preferred by previous customers

- Matched suggested phrases contain queried product type in the end due to the natural order of words in English language phrases (“women shoes”, “michael kors shoes”, “men shoes”, “nike shoes”, “dress shoes”, etc.)

As a starting point, a “bag of words” approach is recommended. Both the query and suggestion phrase tokens are handled irrespective of their order.

This approach is good enough for the majority of cases, but can be improved using advanced ranking techniques discussed in the next section.

How to rank matched suggestions

Ranking by business metrics

The most obvious approach is to rank suggested phrases by the number of search events, which works fairly well. There are, however, a few issues which must be addressed to improve it’s base behaviour:

- After the deduplication procedure is applied, it is recommended to rank each phrase by the whole concept, rather than just the individual phrase. This prevents the ranking to be biased towards concepts which allow less spelling options. For example, “jeans” could be sorted higher than “dresses”, as the former does not allow a singular form.

- A higher number of search events does not necessarily mean a higher business value. Other relevant metrics could be considered in the ranking, such as a number of sales, margin, etc., which affect its business value. If business metrics are collected over a long period of time, it can be useful to boost the value of more recent events.

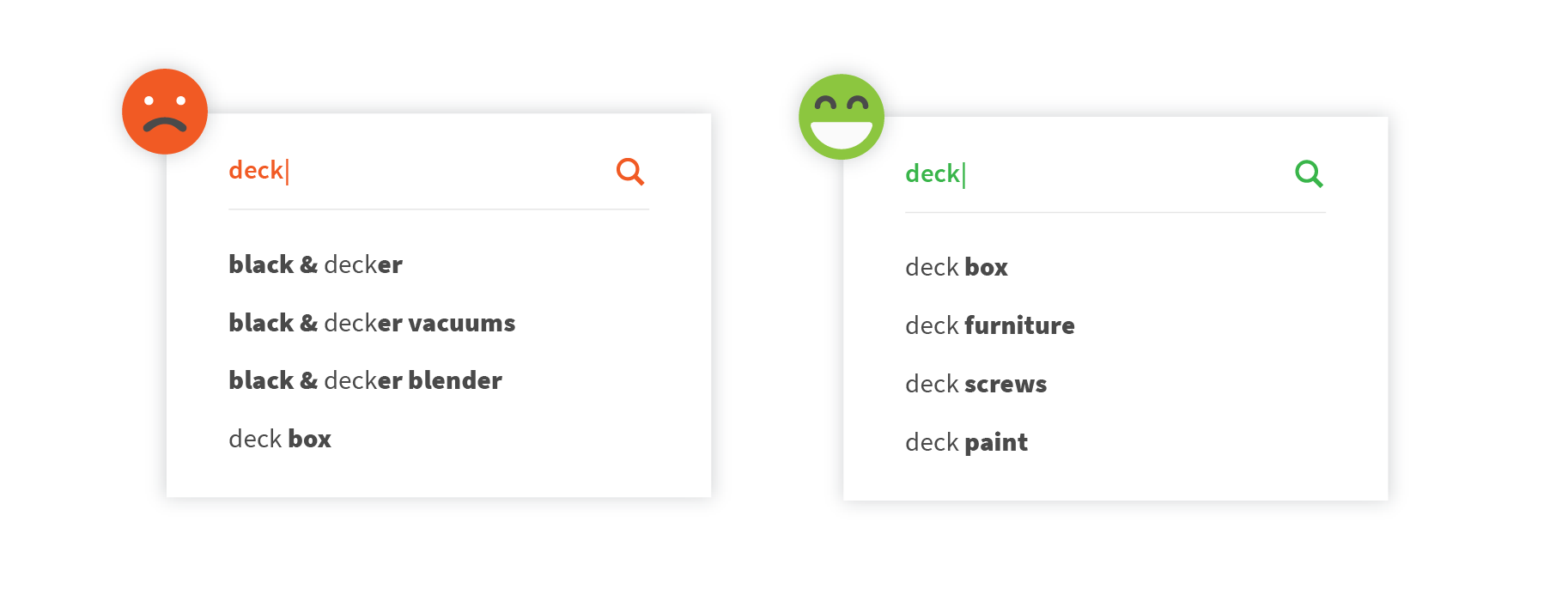

Mitigating issues of the “bag of words” matching model

The “bag of words” matching model works reasonably well, but it has issues in some particular cases

Matching middle tokens

Middle tokens of a of multi-token named entity might be erroneously ranked too high. For example, “deck” is more likely to indicate an interest in “deck furniture”, even if “black & decker” is more popular.

Matching stop words outside of their context

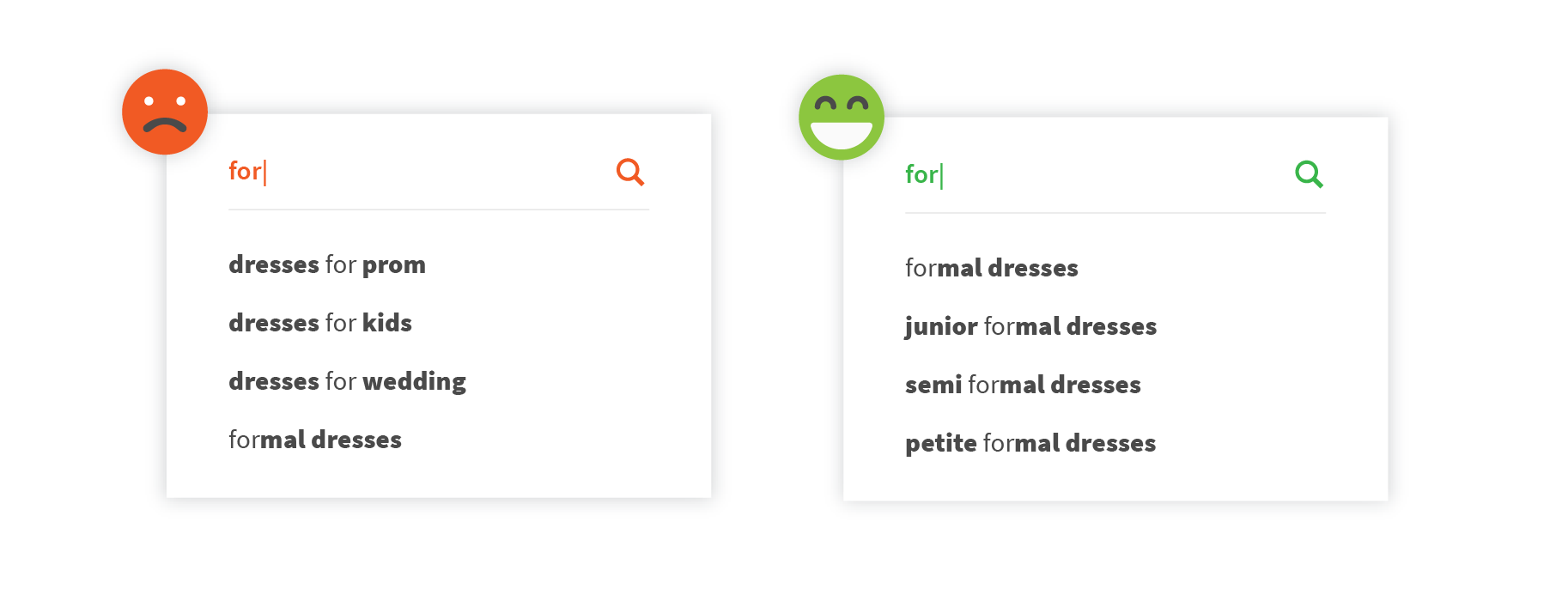

As another example, “for” more likely indicates interest in “formal dresses”, even if “dress for women” is more popular.

Matching multi-word phrases

It is possible to match such multi-word phrases where other semantics exists for a different order of the same words. For example, “dress shi” is more likely to indicate an interest in “dress shirt”, even if “shirt dress” is more popular.

Resolution of such issues may require advanced techniques such as the Learn-to-rank approach or entity tagger, used to tag entity phrases. These entity phrases can then have rank prioritized based on word placement within the phrase. These concepts are beyond the scope of this blog post, and may be discussed in a future blog post.

Other ranking techniques

There are other ranking techniques that can make smart autocomplete ranking more accurate.

Geographic segmentation

Geographic segmentation, or considering the users geographic location can improve ranking results. A user in Florida typing “snow” is more likely to be interested in “snow cone” than “snow blower”.

On-line location

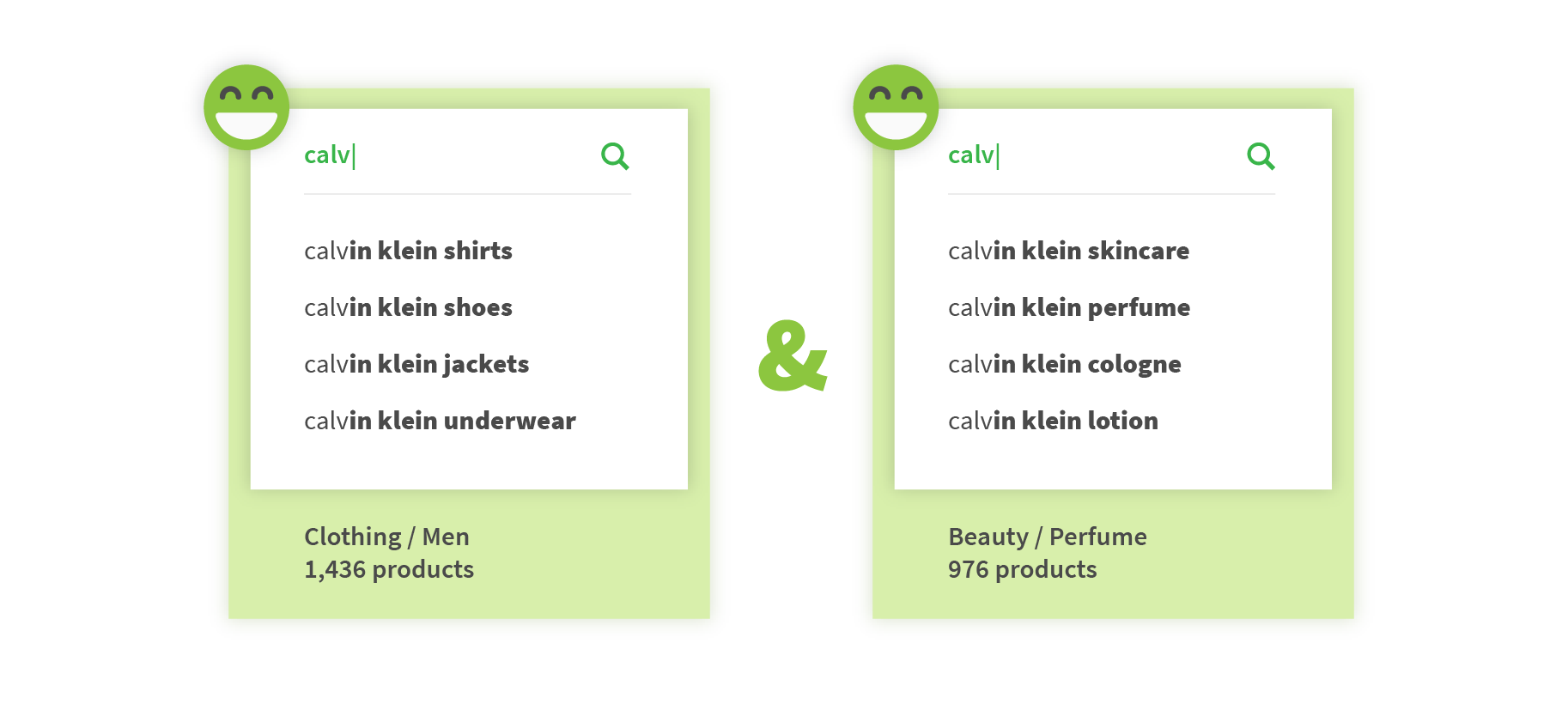

Taking into account the user’s location on the website, can affect phrase ranking. For example, a user typing in “Calvin Klein” while in the menswear section. is more likely to be interested in Calvin Klein shirts, rather than Calvin Klein skincare.

How to present results to the user

Highlighting

Implement highlighting of the displayed suggested phrases indicates which part of the phrase was actually input by the user. The display should highlight all of the matches of the “bag of words” model.

Keyboard navigation

Allow your customers to interact with the suggestions list using a keyboard:

- Use the up/down arrow keys for navigating the list

- Use the enter key for selecting a list item and triggering a search

- Populate the search box with the focused suggestion phrase while navigating to give the user the opportunity to update the phrase on the fly

- Reset the search box to the original typed phrase when the user returns to the search box

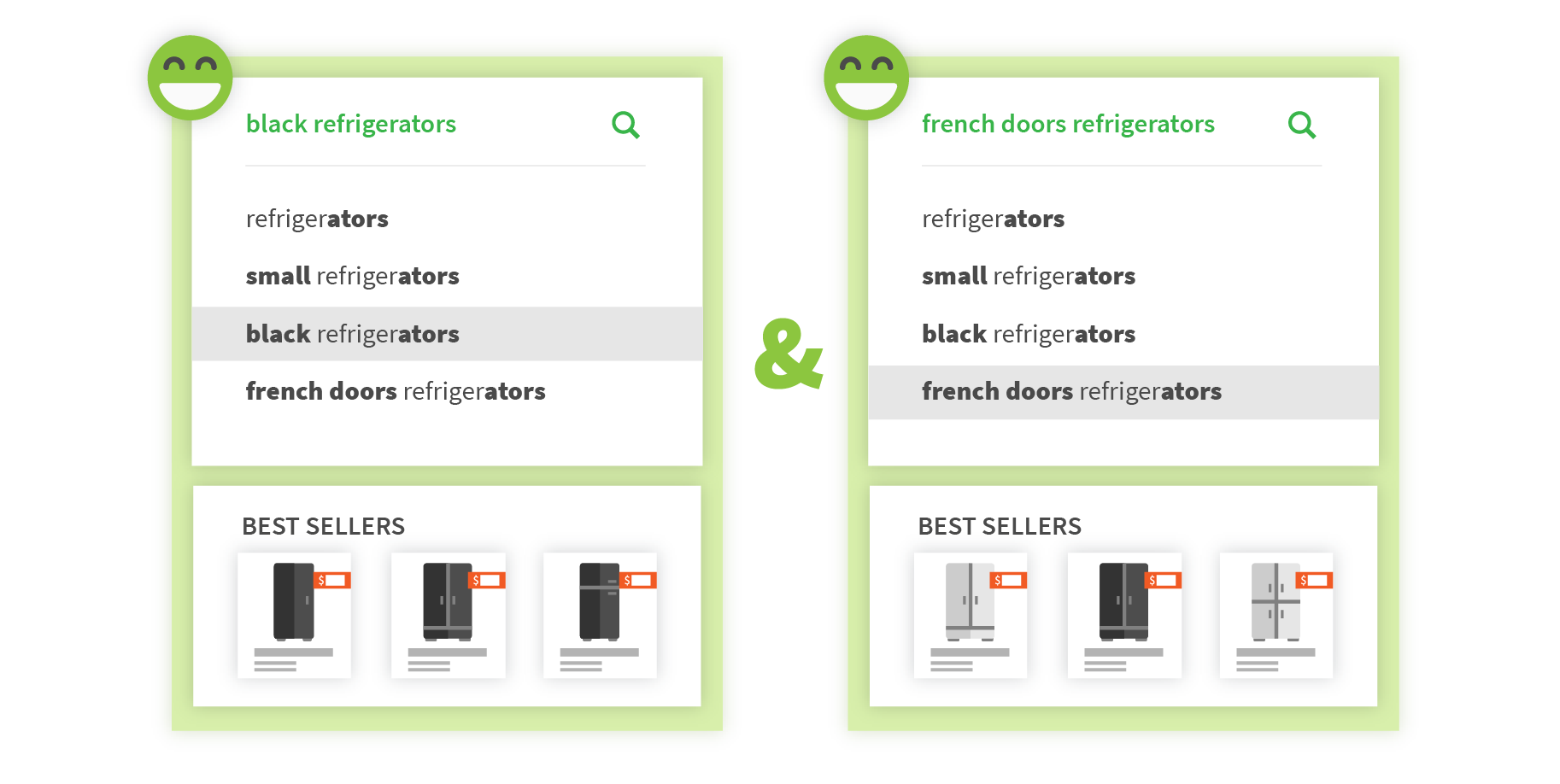

Instant search

While a user navigates through the suggestion list using a keyboard, instant search can show the top few products for a currently selected suggestion. This can be used to make a shortcut from product discovery directly to checkout. It also gives the opportunity to explain meanings of suggested phrases. For example, if a user is searching “refrigerators”, autosuggest can list “french door refrigerators” - which may also include a drawing of a french door refrigerator, so the user understands its meaning.

Conclusion

Smart autocomplete, or autosuggest, can be a powerful discovery tool when implemented correctly. This blog post introduces smart autocomplete, and how it can improve your search experience. It also explains how to build a phrase corpus from a customer search log approach, and then demonstrates smart autocomplete best practices in displaying and ranking suggestions for a user query.

Overall, retailers need a smart autocomplete solution to anticipate a customer’s search intent, and provide useful suggestions. These suggestions will help guide the customer through the product discovery experience, and remove barriers to finding new products online. Investing in these features will consistently improve online conversion rates, and the size of online shopping carts, especially on mobile devices. Given the high impact from this feature, retailers with a large online catalog are essentially leaving money on the table without a powerful smart autocomplete solution.