In-Stream Processing service blueprint

This article introduces the Grid Dynamics Blueprint for In-Stream Processing. It is based on our experience and the lessons we have learned from multiple large-scale client implementations. We have included cloud-ready configuration examples for Apache Kafka, Spark, Cassandra, and Zookeeper, plus Redis and HDFS.

Blueprint goals

This Blueprint aims to address a number of architectural goals we’ve heard repeatedly from our customers, who are CTOs and Chief Architects of Big Data systems:

- Pre-integrated: The overall Blueprint represents an integrated In-Stream Processing Service, built from many software components, that can be designed, deployed and managed as a single service.

- 100% free, open, and supported by an active community: All components of the Blueprint are major open source software projects under active development by a vibrant and diverse community of contributors that includes both vendors and end users. The Blueprint itself is also free and open.

- Cloud-ready: Designed to be dynamically scalable and deployable on cloud infrastructures.

- Portable across clouds: Designed to run on any cloud, free from proprietary cloud vendor APIs or other lock-ins that would inhibit portability.

- Production-ready: The blueprint provides production-ready operational configurations for all components and the entire integrated service.

- Proven in mission-critical use: All components are considered “mainstream” and have been proven in multiple, successful large-scale implementations in the industry, as well as by other Grid Dynamics customers.

- Interoperable with any Big Data platform: In-Stream Processing can be deployed as a stand-alone cloud service and integrated with any Big Data platform via APIs.

- Extendable: Individual components, interfaces or APIs in the Blueprint can be replaced, modified or extended by the customer’s architects to adapt to their specific needs. By its very nature, a Blueprint is a reference design that provides a solid foundation for the architecture team to build upon.

Blueprint scope

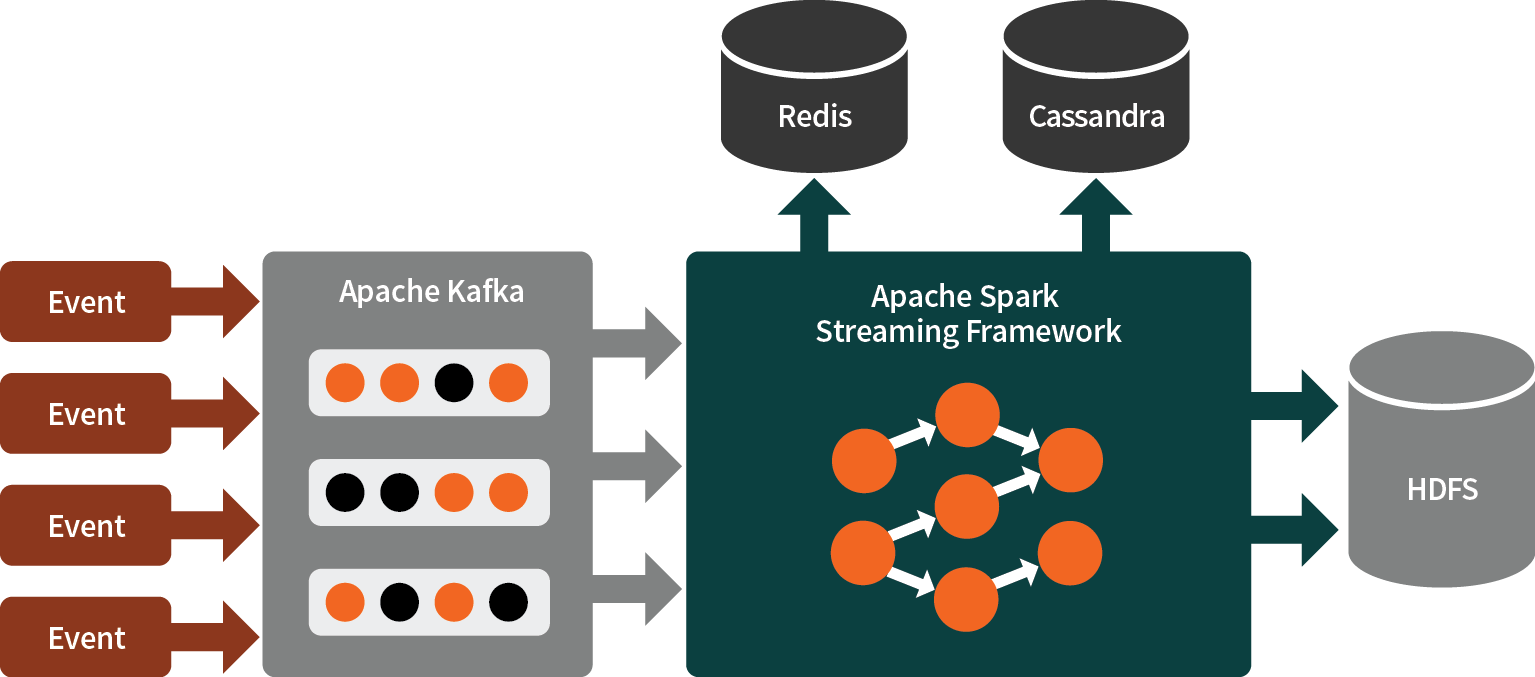

In the current version of the Blueprint, we pre-integrated a number of technologies (outlined in this post) that, together, make up an In-Stream Processing stack:

- Persistent message queue system: Apache Kafka

- In-Stream Processing framework: Spark Streaming

- Lookup database: Redis

- Operational store: Cassandra

- Delivery of ingestions: HDFS

The Blueprint also addresses a number of operational concerns:

- Scalability of each component, and the overall service

- Availability of each component, and the overall service

- Delivery semantics ensured by the service during failure conditions

Operational design for scalability and reliability

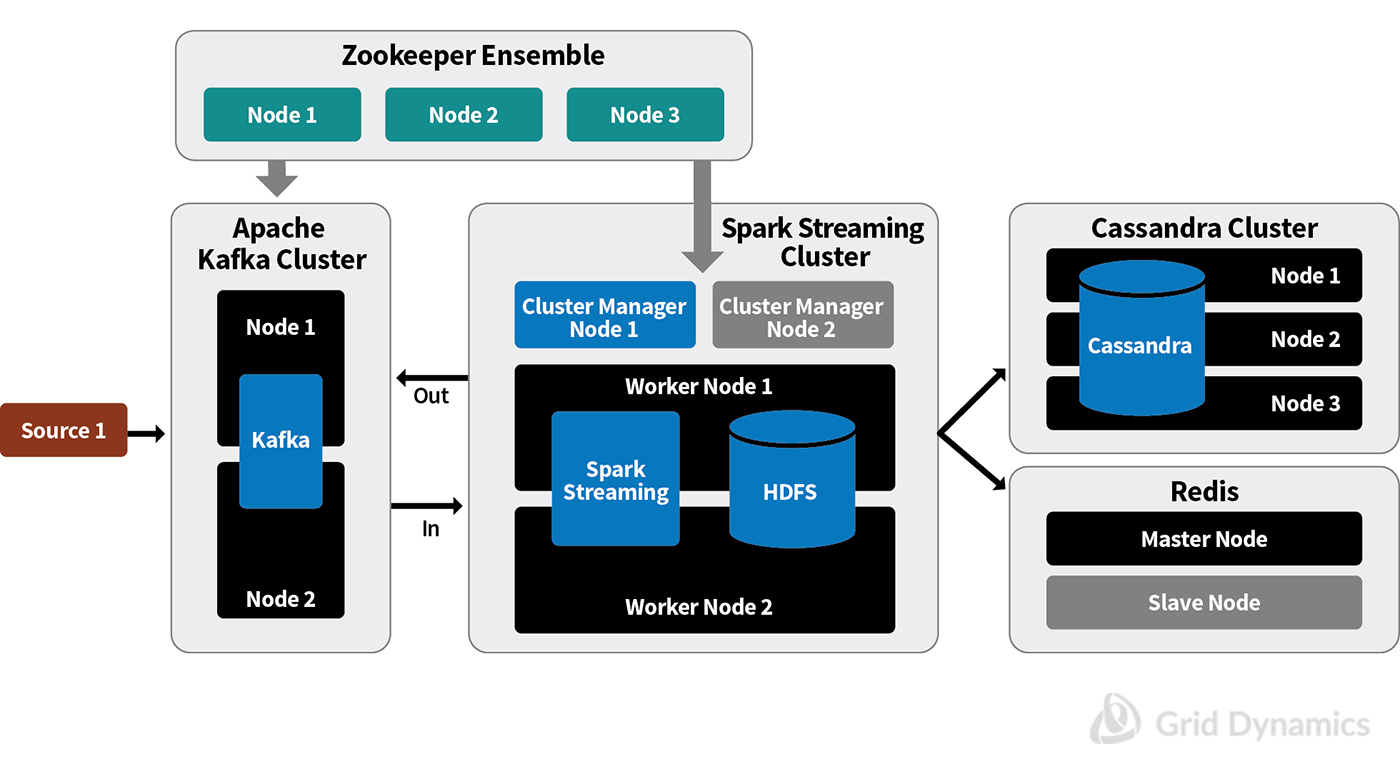

We start by describing a distributed, fault-tolerant computing system architecture that is highly available with respect to a failure of any node or functional component of the Blueprint. The diagram below shows the minimum cluster configuration that can be scaled up to meet actual business demands:

If any single node fails, the system in the diagram above will still be fully functional. The diagram below shows which nodes could fail simultaneously without a negative impact on our In-Stream Processing service's functionality. There won’t be any performance degradation if the virtual machines are sized correctly to handle the complete workload in an emergency situation.

One point worth noting is that the absence of a single point of failure makes the system tolerant of many — but not all — kinds of failures. For example, systems distributed across several data centers indirectly include communication subsystems that are not under the direct control of a Data Center or a Platform as a Service (PaaS) provider. The number of possible deployment configurations is so large that no single recipe can be universal enough to address all non-specific fault tolerance problems. That said, the presented architecture is able to ensure 99.999% reliability in most cases.

Another important aspect of reliability is the delivery semantic. In the strictest case every event must be processed by the streaming service once, and only once. An end-to-end ability to process all the events exactly once requires:

- Ability to re-emit source data in case of a failure during data processing

- Ensuring that all communications between these components are safe from data losses

- Idempotence of the data consuming method on the downstream system.

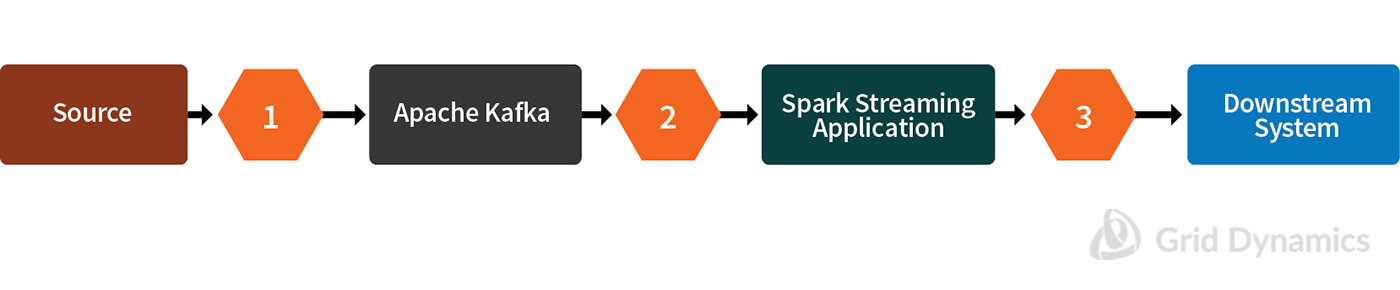

The idempotency requirement means the downstream system has to tolerate data duplication. See the diagram below:

Data transmission reliability to (communication point #1) and from our In-Stream Processing Service (communication point #3) requires certain behaviors from components external to the Blueprint. Specifically, the source and downstream systems should deliver and consume events in a synchronous way.

Apache Kafka and Spark Streaming ensure that data will be processed without losses once it is accepted for processing. Simply speaking, failures inside the Spark Streaming Application are automatically handled by re-processing the recent data. It is achieved by Apache Kafka’s capability to keep data for a configurable period of time up to dozens of days (communication point #2).

Operational Apache Kafka configuration

Getting an optimal configuration for Apache Kafka requires several important design decisions and careful trade offs between architectural concerns such as durability and latency, ease of scaling, and cost of overhead.

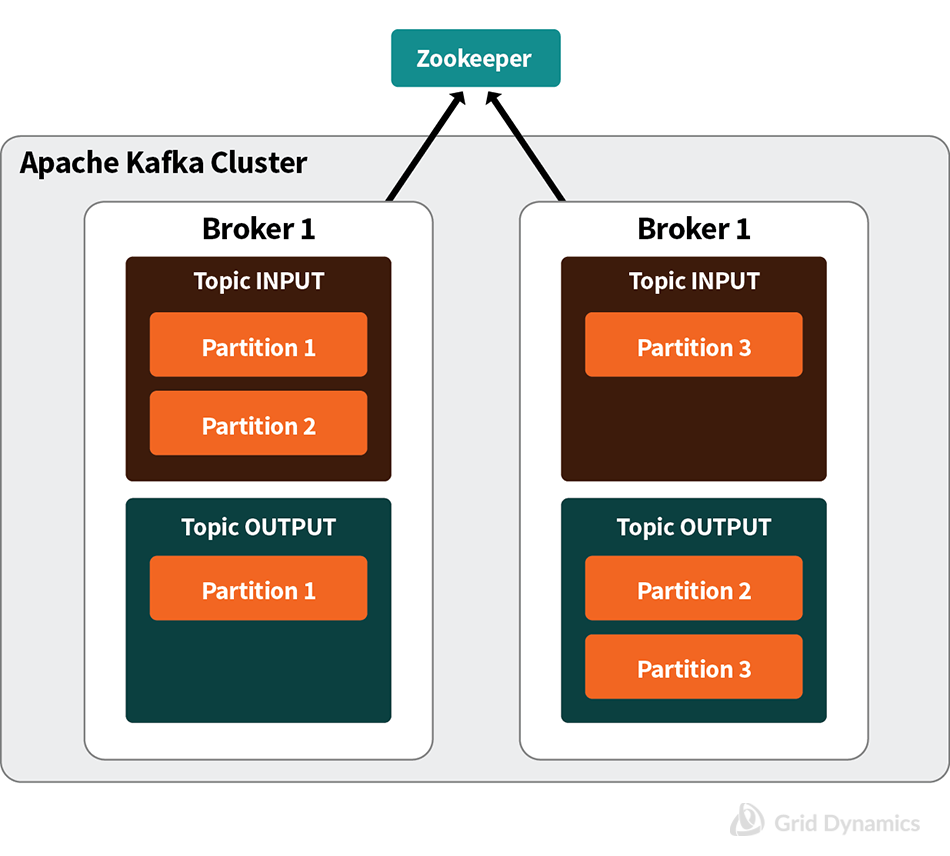

First, let’s start with durability concerns. Apache Kafka is run as a cluster of brokers. One cluster can contain many logical channels called queues or topics, each split into multiple partitions. Each partition is replicated across brokers according to a replication factor configured for durability. As a result, each broker is responsible for a number of assigned partitions and replicas. Coordination of re-assignments in case of failures is provided with Apache ZooKeeper.

Data replication and persistence together deliver “pretty good” immunity from data loss. But as with all distributed systems, there is a trade off between latency and the system’s level of durability. Apache Kafka provides many configuration options, starting with asynchronous delivery of events from producers in batches and ending with synchronous publishing of every event blocking until the event is committed, i.e. when all in sync replicas for the partition have applied it to their logs.

Asynchronous delivery clearly will be the fastest. The producer will receive an immediate acknowledgment when data reaches the Kafka broker without waiting for replication and persistence. If something happens to the Kafka broker at that moment, the data will be lost. The other extreme is full persistence. The producer will receive an acknowledgment only after the submitted events are successfully replicated and physically stored. If something happens during these operations, the producer will re-submit the events. This will be the safest configuration option from a data loss standpoint, but it is the slowest mode.

The next important aspect of Apache Kafka configuration is choosing the optimal number of partitions. Since repartitioning the message queue is a manual process, it is highly disruptive to service operations because it requires downtime. Ideally, we shouldn’t need to do this more frequently than once a year; however, to maintain stable partitioning for this long requires solid forecasting skills.

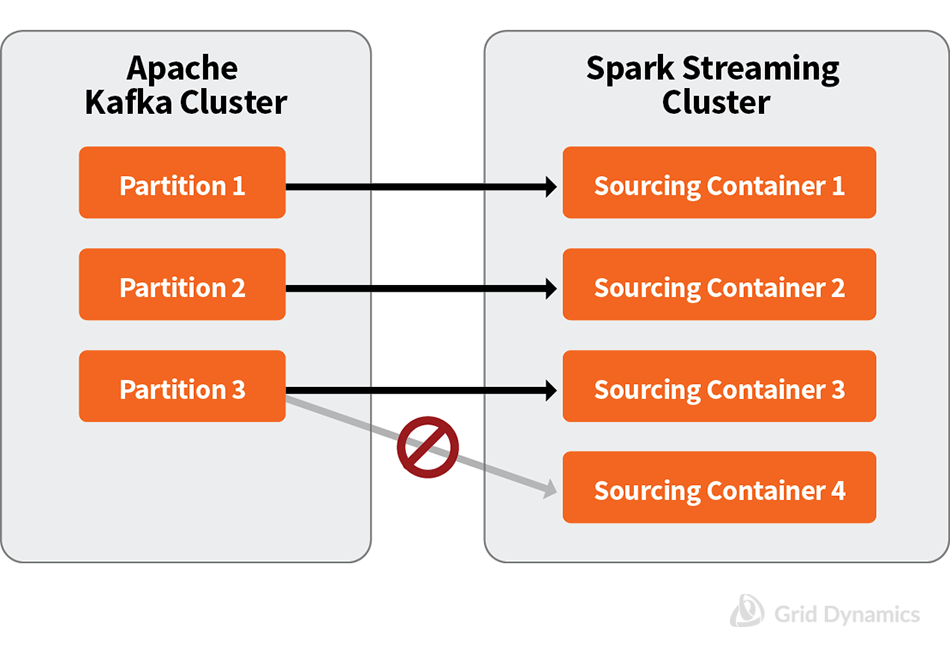

In a nutshell, getting partitioning right is a combination of art and science directed at finding a balance between ease of scaling and the overhead cost of over-partitioning. More partitions bring higher overhead and impact memory requirements, ZooKeeper performance, and partition transitioning time during failover. On the other hand, since a partition is a unit of parallelization, the number of partitions should be sufficient to efficiently parallelize event handling by the message queue. Since a single Kafka partition must be consumed by a single sourcing container in a Spark Streaming application, the number of partitions also heavily affects overall throughput of event consumption by the sourcing containers. The advantages and drawbacks of over-partitioning are described in this blog post from the Apache Kafka designers.

The illustration above shows how, for efficient topic partitioning, we should estimate the number of partitions. It should be the minimum number sufficient to achieve:

- The necessary level of events consumption parallelization in Spark Streaming applications

- The ability to handle an increasing workload without repartitioning

The process of finding an optimal parallelization level for a Spark Streaming applications is, again, a mixture of art and science. It is an iterative process of application tuning with many forks and dependencies that is highly dependent on the nature of the application. Sadly, no “one-size-fits-all” methodology has emerged that can substitute for hands-on experience.

Finally, we will provide a few thoughts on hardware configuration for Kafka. Since Kafka is a highly-optimized message queue system designed to efficiently parallelize computing and I/O operations, it’s crucial to parallelize storage I/O operations since they are the slowest part of the system, especially with random data access. An important Apache Kafka advantage is its ability to keep the raw events stream for several days. For example, in case of 300K events per second, 150 bytes per event, the data size for seven days will be about 24 TB. Kafka provides per-event compression which can cut storage requirements, but compression impacts performance — and, in any case, the actual compression ratio depends on the events format and content.

Operational ZooKeeper ensemble configuration

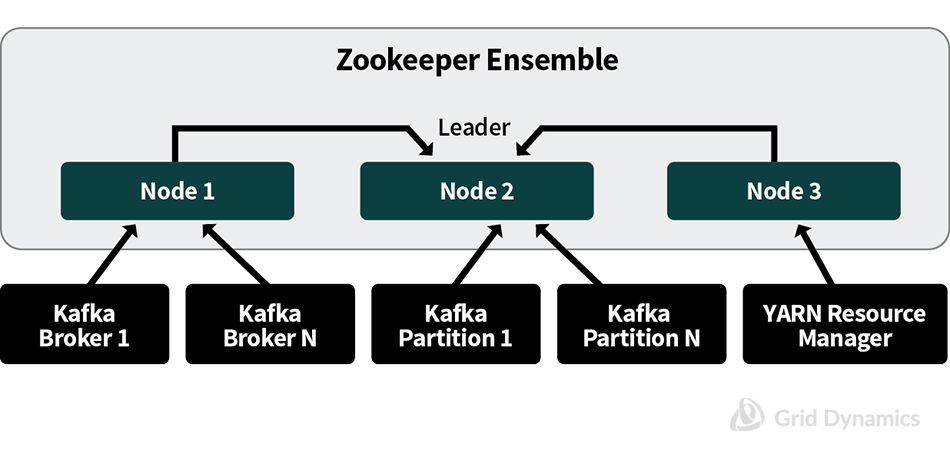

ZooKeeper is a distributed coordination service used to achieve high availability for Apache Kafka partitions and brokers, as well as a resource manager for the Spark Streaming cluster. Apache ZooKeeper lets distributed systems follow services, which facilitates overall high availability: it provides guaranteed consistent storage for the state of a distributed system, client monitoring, and leader election.

Previous versions of the Spark API for Apache Kafka integration used ZooKeeper for managing consumer offsets, which almost always turned ZooKeeper into a performance bottleneck. Nowadays, with the introduction of a Direct Apache Kafka API in Spark, consumer offsets are best managed in checkpoints. In this case, one ZooKeeper ensemble can be shared between the Message Queue and the Stream Processing clusters with no compromise in performance or availability, while substantially reducing administration efforts and cloud resources.

A ZooKeeper ensemble consists of several, typically three to seven, identical nodes that each have dedicated high speed storage for transaction persistence. ZooKeeper works with small and simple data structures reflecting the cluster state. This data is very limited in size. Therefore RAM and consumed disk space are almost independent of the event flow rate and may be considered constant for all practical purposes.

ZooKeeper performance is sensitive to storage I/O performance. Considering that ZooKeeper is a crucial part of the Kafka ecosystem, it’s a good idea to run it on dedicated instances or at least to set up a dedicated storage mount point for its persistent data.

Operational Spark Streaming configuration

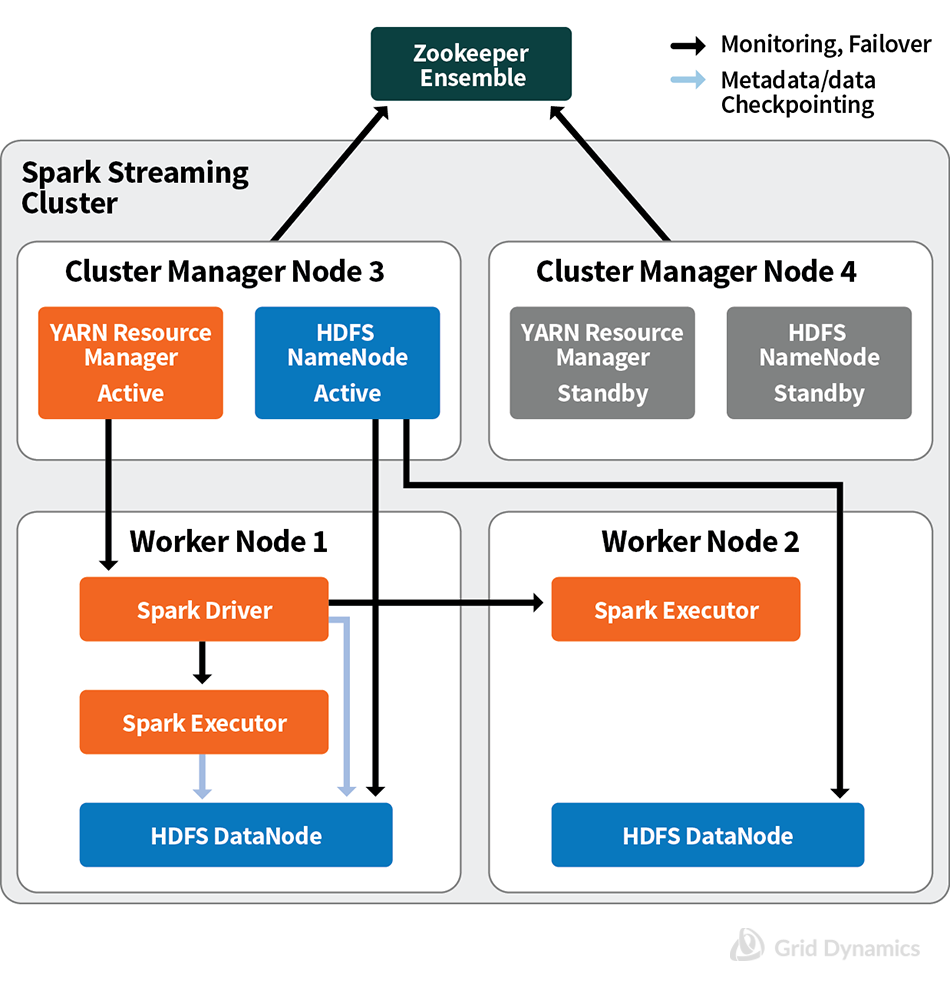

Here is a fault-tolerant Spark Streaming cluster design. It addresses three reliability aspects: zero data loss, no duplicates, and automatic failover for all component-level failures. The next diagram shows a five-component sub-system where each component must be highly available:

- Resource Manager

- Spark Driver

- Spark Executor

- HDFS NameNode

- HDFS DataNode

- The YARN ResourceManager is responsible for tracking resources in a Spark Cluster. High Availability is achieved via Active/Standby architecture, where the ZooKeeper ensemble is used for active resource manager selection.

- The Spark Driver is a component of a user application that coordinates launching all separate tasks of the application on a cluster nodes. The Spark Driver periodically checks its state in HDFS. When the Driver dies, all the data being processed by all live Executors will be lost. Therefore, after the Driver restarts, all that data has to be reprocessed. YARN’s Resource Manager restarts the Driver in case of failures. After the restart, the new instance of the Driver recovers its state from a checkpoint stored in HDFS.

- Spark Executor is a component of a user application performing data processing. It’s highly available by design of the Spark Streaming framework. If an Executor dies, the Driver starts another one and reprocesses all data lost by the now-dead Executor.

- HDFS NameNode is an HDFS cluster manager. Its high availability is achieved via Active/Standby architecture similarly to the YARN ResourceManager described above. A ZooKeeper ensemble is also used to select an active namenode.

- An HDFS DataNode is a component of an HDFS cluster responsible for read/write requests from the filesystem’s clients. It is highly available due to the HDFS cluster’s design. If a DataNode dies, the NameNode redistributes its data blocks across other DataNodes.

The next aspect of reliability is the assurance of zero data loss and no duplications. Typical message delivery semantics recognize three types of requirements:

- At Most Once: Each record will be either processed once or not processed at all.

- At Least Once: Each record will be processed one or more times. This is stronger than At Most Once as it ensures that no data will be lost, but there may be duplicates.

- Exactly Once: Each record will be processed exactly once - no data will be lost and no data will be processed multiple times.

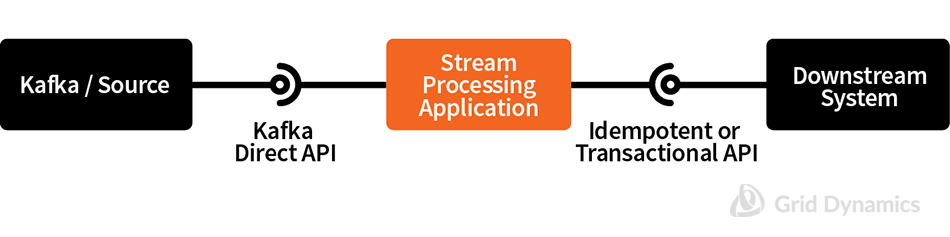

In-Stream Processing applications are often required to support Exactly Once delivery semantics. While it is possible to achieve an end-to-end Exactly Once semantic for most In-Stream Processing applications, comprehensive discussion of this topic deserves a separate article. Here, we’ll briefly mention the main approaches, starting with the diagram below:

As previously mentioned, Kafka has the ability to replay the stream, which is important if there is a failure. A replay of recent events is automatically triggered in case of a failure inside the Stream Processing Application, whether it is caused by hardware or software. “Recent events” in this case means micro-batches that were emitted but not successfully processed. At Least Once delivery semantics are achieved by doing this. Exactly Once requires additional effort which either involves In-Stream events deduplication (i.e. looking up processed event identifiers from an external database) or by designing an idempotent method of insight consumption by downstream systems. The last option simply means the downstream system is tolerant of duplicates; i.e. two equal REST calls, one of which is duplicated, will not break consistency.

Operational Cassandra configuration

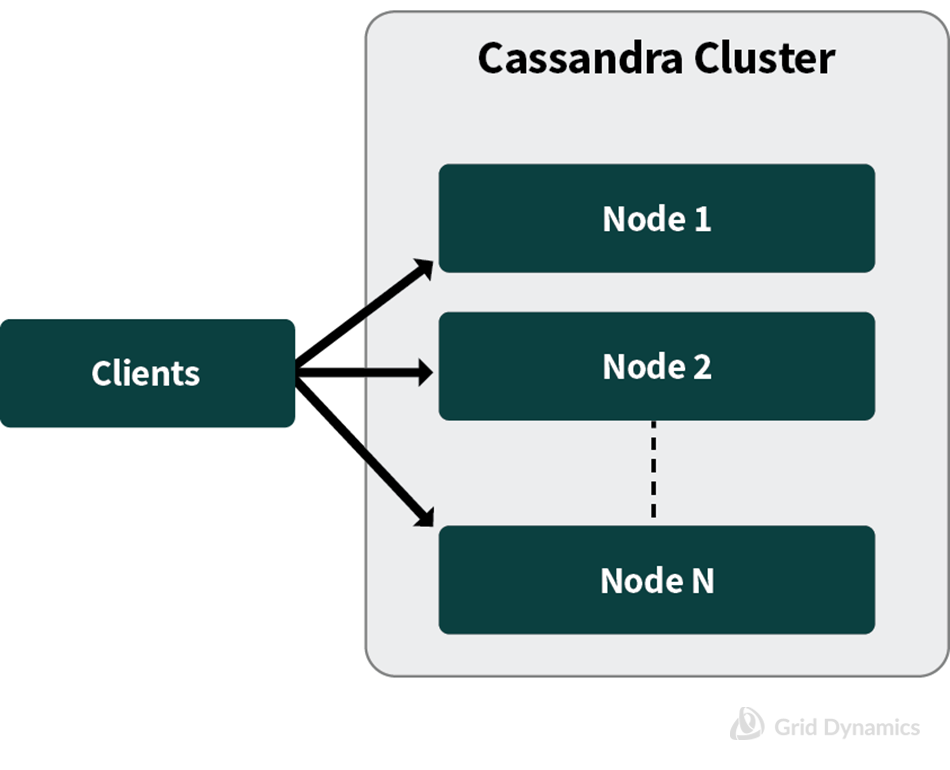

Cassandra is a massively scalable, highly available NoSQL database. A Cassandra cluster consists of peer nodes with no dedicated cluster manager function. That means any client may connect to any node and request any data, as shown on this diagram.

The minimum highly available Cassandra cluster consists of 3 (three) nodes, where replication factor is 3 (three), with 2 (two) read and write replicas. With fewer nodes, a node failure will block read or write operations if the database was configured to ensure data consistency.

Cassandra allows you to tune its durability and consistency levels by configuring the replication factor (RF) and the number of nodes to write (W) and read (R). In order for the data to be consistent, the following rule has to be fulfilled: W + R > RF.

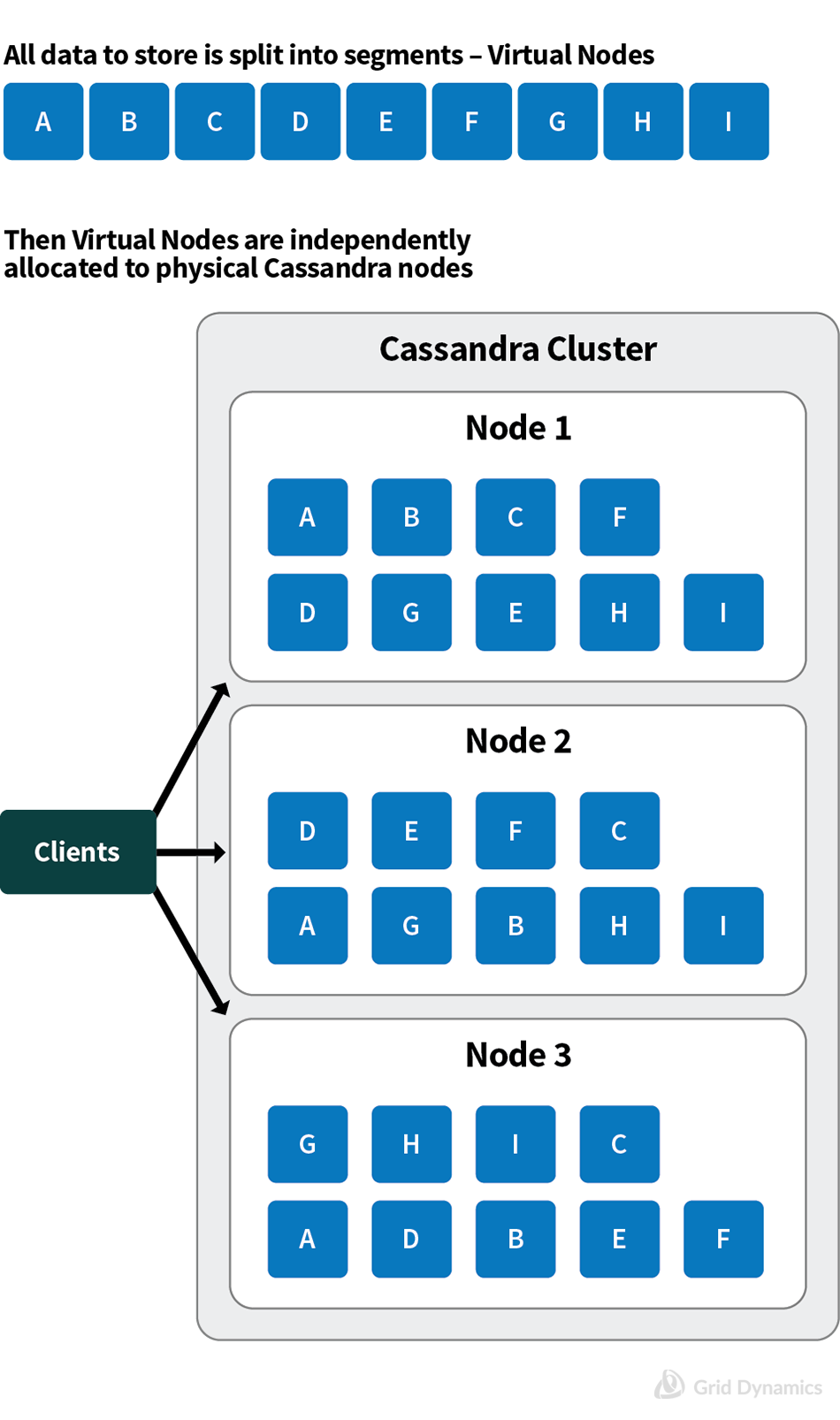

Durability is achieved via data replication. The Virtual Node (VN) concept is essential for understanding how data replication works. As we have said, a regular Cassandra cluster consists of several homogenous nodes. The dataset is split into many segments, called Virtual Nodes. Each segment is replicated several times according to the configured replication factor, as seen in the diagram below:

Hardware failures, generally speaking, result in data inconsistency in replicas. Once a failed node comes back online, a repair process is started that restores replica consistency. The repair process has automatic and manual options. If the failed node is considered permanently down, the administrator has to remove it manually from the cluster.

Another aspect of durability is data persistence. Cassandra employs commit logs. Essentially, all writes to a commit log are cached like any other storage I/O operation. The data is truly persisted only after it is physically written to storage. Since such operations are time-consuming, the commit log is synced periodically — every so many milliseconds — based on parameters specified in the configuration. Theoretically, the data not synced with physical storage might be lost due to problems such as a sudden power outage. In practice, data replication and power supply redundancy make this situation very unlikely.

Operational Redis configuration

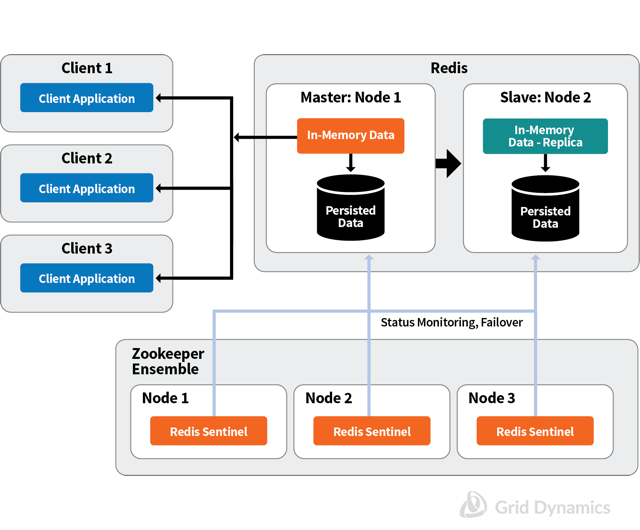

Redis was originally written in 2009 as a simple, key-value, in-memory database. This made Redis very efficient for read operations with simple data structures. Since then, Redis has acquired many additional features including sharding, persistence, replication, and automatic failover. This has made it an ideal lookup datastore. Since lookup data volumes are usually rather small, we rarely see a necessity for data partitioning for scalability with Redis. The typical HA Redis deployment consists of at least two nodes. Availability is achieved with Master-Slave data replication. Redis includes an agent called Sentinel that monitors data nodes and performs the failover procedure when the Master node fails. Sentinel can be deployed in various ways; the documentation provides information about the advantages and pitfalls of different approaches. We suggest deploying Sentinel to ZooKeeper nodes, as shown in the following diagram:

The number of running Sentinel instances must be greater than two since each Sentinel agent can start a failover procedure after coordination with a majority of agents.

Redis is very performant database and it’s very unlikely that the CPU will become a bottleneck, any more than memory will for the “lookup database.” However, if the CPU becomes a bottleneck, scalability is achieved via data sharding. Redis is a single-threaded application, so multiple CPU cores can be utilized with data sharding and by running several Redis instances on the same VM. In sharding mode, Redis creates 16384 hash slots and distributes them between shards. Clients may still request data from any node. In case a request comes to a node that doesn’t have the requested data, it will be redirected to the proper node.

Durability is achieved with data persistence. Here, Redis provides two main options: a snapshot of all user data as an RDB file, or log all write operations in an AOF (Append-Only File). Both options have their own advantages and drawbacks, which are described in detail in the official documentation. (In our experience we have found that the AOF method provides higher durability in exchange for slightly more maintenance effort).

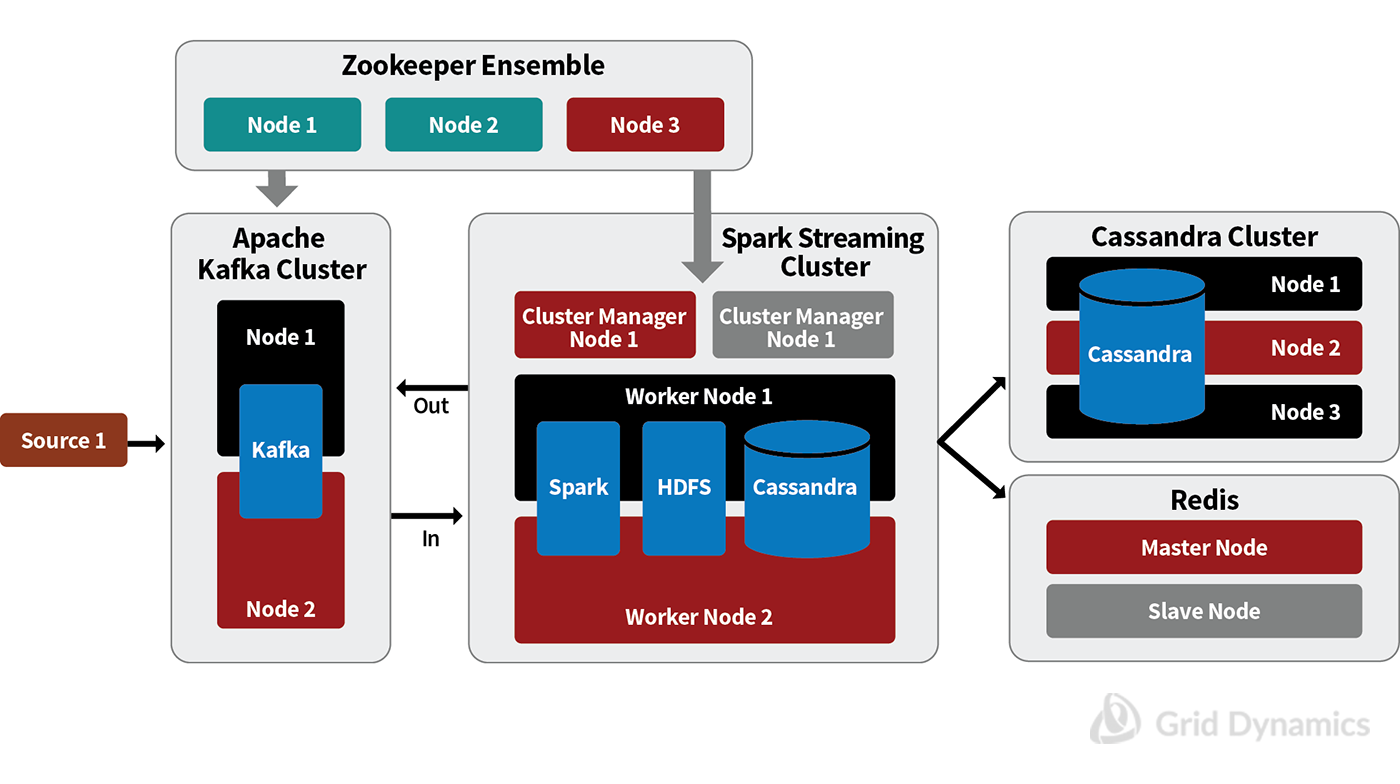

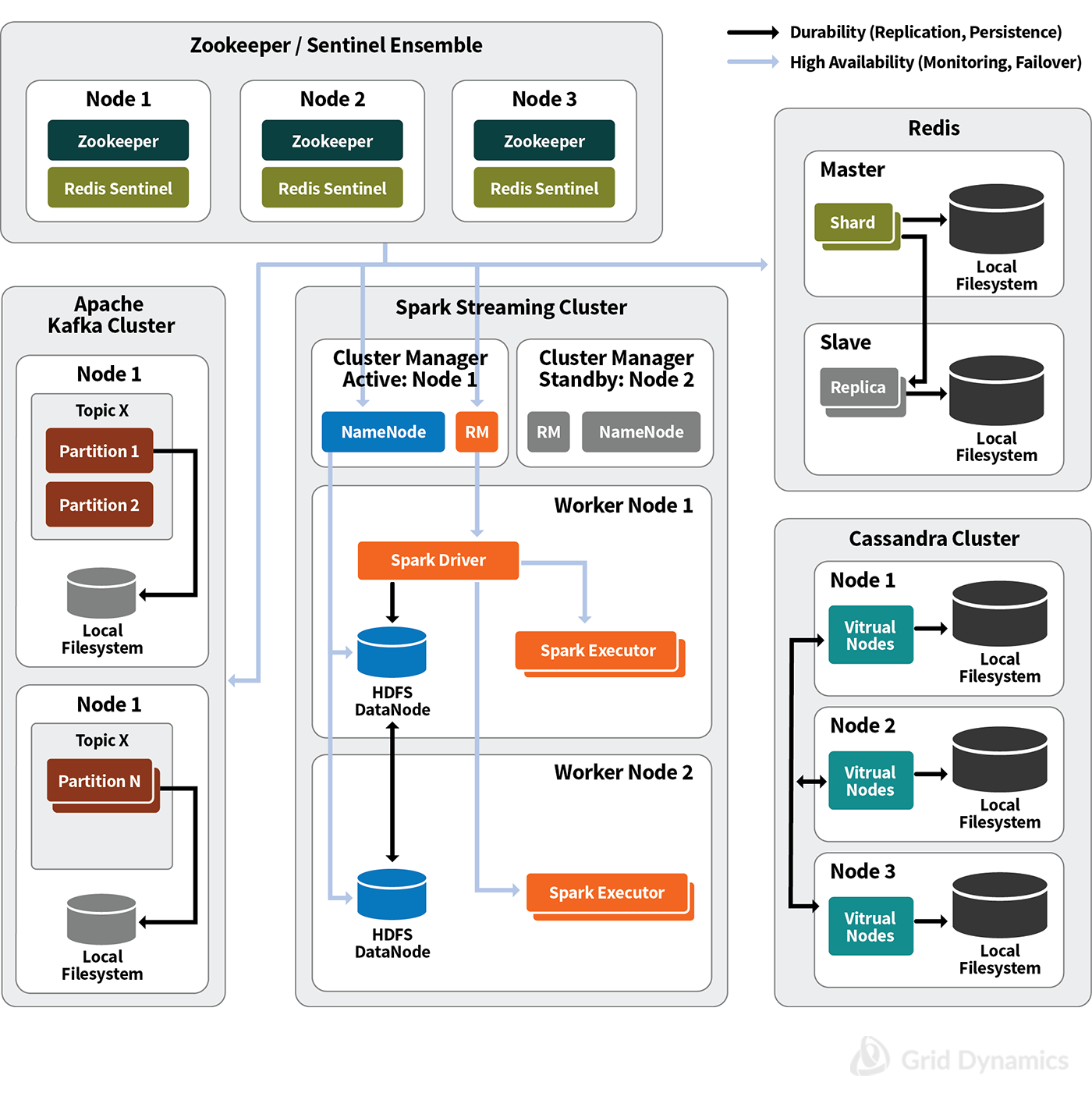

End-to-end operational configuration

Now that we have analyzed each component separately, it is time to display a single “big picture” diagram that shows the complete, end-to-end topology of a scalable, durable and fault-tolerant In-Stream Processing service design:

Summary of target SLAs addressed by the blueprint

To summarize the capabilities of our In-Stream Processing service, these are the SLAs targeted by the design we have presented here:

- High-throughput (up to 100,000 events per second), low-latency (under 60 seconds) processing of data streams

- Fault-tolerant, highly available, dynamically scalable computational platform

- Supports all algorithms supported by Spark Streaming, including Spark SQL Streaming and online machine learning

- Supports programming logic written in Spark Streaming APIs in Java or Scala

- Includes lookup and operational stores for different needs, including intermediate and final results storage

- The actionable insights will be delivered via REST API online

- If there is a downstream system designed to handle a stream of insights, the results will be delivered via a message queue

- All bulk throughput will be written into a cloud file system. If target post-processing systems are remote, such as Hadoop/ HDFS clusters, they will be updated via batch upload from the cloud file system. If Hadoop is local to the cloud, integration with HDFS is supported out-of-the-box.

- All raw data and results will be archived for 30 days on the cloud file system

- Built-in mechanism to suspend the load and resume after upgrade with service interruptions of less than 30 seconds during upgrade — with no data loss

This blueprint doesn’t cover everything

Several important architectural and operational concerns are not addressed by this version of our Blueprint, such as:

- Design of data lakes, batch processing or online systems that utilize the insights from the In-Stream Processing Service

- Tools and modeling environments for Data Scientists

- How source events are delivered to the message queue

- Dashboards for visualization, monitoring, and reporting of In-Stream Processing results

- Logging and monitoring

- Authentication and authorization

- Data encryption, in motion or at rest

- Infrastructure provisioning and deployment automation

- Upgrades and patching

- Multi-datacenter architecture

- Disaster recovery

- Continuous integration and continuous delivery pipeline

- Test data strategy

- Testing and simulation

The usual reasons for exclusion include:

- No applicable general-purpose, proven open source technology exists at the time of writing

- No proven, repeatable best practice has emerged at the time of writing

Solutions are usually specific to each customer environment - Not a part of the In-Stream Processing itself, even thought it might be a part of a bigger Big Data landscape

- The scope of the Blueprint would expand too much to be practical

- Will be added to future versions of the Blueprint

If you have a question you’d like to ask, we’d be happy to share what we’ve learned. Please leave a question in the comments or send us a note.

References

- Reliable Spark Streaming

- Can Spark Streaming survive Chaos Monkey?

- Improved Fault-tolerance and Zero Data Loss in Spark Streaming

- Apache Kafka Documentation

- ZooKeeper documentation

- Apache Cassandra documentation

- Redis documentation

- Redis Sentinel essentials

- YARN’s ResourceManager High Availability

- HDFS documentation: Architecture Guide

- HDFS documentation: High Availability

- Edureka! blog: how to Set Up Hadoop Cluster with HDFS High Availability

- Zen and the Art of Spark Maintenance with Cassandra

- Cassandra and Spark: Optimizing for Data Locality

- Lambda Architecture with Spark Streaming, Kafka, Cassandra, Akka, Scala

- Benchmarking: Apache Cassandra, Couchbase, HBase, and MongoDB

- How Redis is used in Stack Overflow

- Redis persistence in practice

- How to enable High Availability on Spark with ZooKeeper

- Tuning Spark Streaming Applications

Sergey Tryuber, Anton Ovchinnikov, Victoria Livschitz